By Jim Wiegand

March 14, 2012 (San Diego’s East County)--A recent study from Spain estimates bird mortality to be 6-18 million birds and bats annually from their 18,000 installed wind turbines with an installed capacity of 20,676 MW. This works out to a staggering total of 333-1000 birds and bats per turbine or 290-871 mortalities per MW for wind energy in Spain. In America, on the AWEA web site the reported bird death rate from wind turbines is 2.9 fatalities per MW.

These numbers from Spain are several hundred times more than the reported mortality from the wind industry in America. There is a reason for this disparity. It is because of wind industry interference. It has been going on for the last 28 years and still to this day, there has not been a properly conducted bird mortality study done in America.

To fully understand this cover-up, I am going to take a look back to the beginnings of the wind industry. Because what took place in the 1980's set the industry on a path that they still tread on today.

My discussion of the condor from the early 1980's will bring to light a combination of facts and circumstances never before disclosed about the wind industry. What happened to the condor is part one of a two part investigation into the 28 year bird mortality cover-up by the wind industry.

In 1980 the wind industry was just beginning to set roots in California. Wind energy was a new frontier, a new technology and investors saw a great opportunity to reap profits. During that same time the struggling condor population, by best estimates, was down to only 25 to 35 condors left in the  wild. The small population of condors was considered to be somewhat stable even though it was severely endangered. Their small numbers had been hanging on for several decades but they were declining. But their exact numbers were in question because their huge foraging territories covered several thousand square miles and researchers weren't sure which birds they were seeing at any given location.

wild. The small population of condors was considered to be somewhat stable even though it was severely endangered. Their small numbers had been hanging on for several decades but they were declining. But their exact numbers were in question because their huge foraging territories covered several thousand square miles and researchers weren't sure which birds they were seeing at any given location.

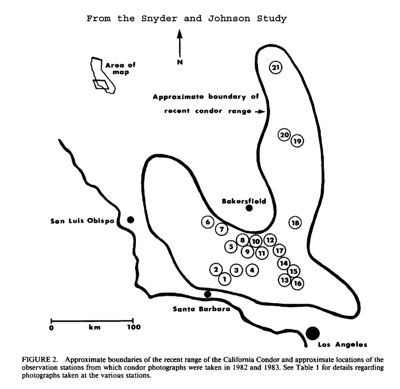

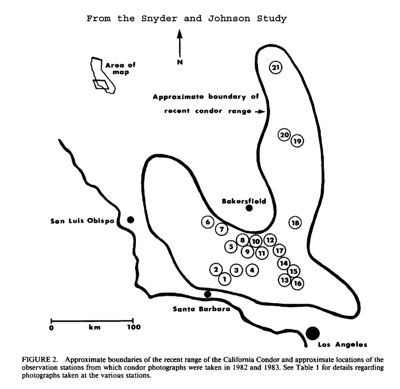

In 1982 two researchers, Noel Snyder and Eric Johnson, set out to get exact condor numbers by setting up 21 different stations in their foraging habitat. This was done so they could get photographic details of every condor that would provide distinguishable characteristics of all the individual condors. In 1982 they estimated 21-24 condors. The next year from data taken up to October 30 1983 they estimated 19-22 condors remaining, documenting a decline. In their report they also noted that at the current downward trend, it was projected that the wild condor population would go extinct sometime between 1993 and 2003.

Just 15 months later, in January 1985, reports came in from the field that one or both adult condors were missing from their respective breeding territories. In April another condor was found dead and was determined to have died from lead poisoning. The population was down to only 9 condors and in a short span of just 15 months, the population had dropped by more than 50%. As it was stated later in a FWS document "it was clear that some disaster had struck".

After these catastrophic losses, a decision was made to trap the remaining condors. Eight of the 9 remaining condors were captured and put into captivity.

Was it lead poisoning? It was well documented that exposure to lead was killing condors but this had been going on for decades. While it was most likely the primary reason for their gradual decline over the decades it is not reasonable to think this was the cause for the sudden decline. In fact their exposure to lead fragments had likely decreased over the years because hunting pressure had declined dramatically from the 1950s and early1960's and wounded deer left in the field in their habitat, were far fewer in number. In addition the remaining condors had been receiving clean supplemental food at feeding stations for years. So what did kill off the condors so dramatically and in such a short period of time?

The FWS statement was correct, a disaster had struck. From 1983 through 1985 there was an explosion of wind development which added over five million square feet of spinning wind turbine blades into this same area. At the end of 1982 there were 323 small wind turbines that had been recently  placed in the condor habitat . By the end of 1985 thousands of new and larger wind turbines had invaded their home, which included the Tehachapi Pass wind resource area. Wind developers had increased their footprint with 19 times more rotor sweep so they could take advantage of expiring tax credits that would end at the of 1985. It would prove be the final blow to the condors.

placed in the condor habitat . By the end of 1985 thousands of new and larger wind turbines had invaded their home, which included the Tehachapi Pass wind resource area. Wind developers had increased their footprint with 19 times more rotor sweep so they could take advantage of expiring tax credits that would end at the of 1985. It would prove be the final blow to the condors.

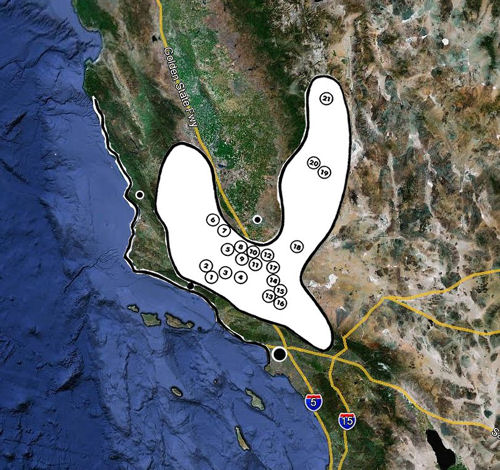

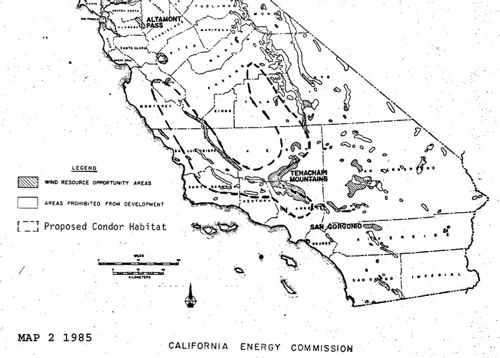

We know for certain that wind turbines slaughter all species of birds and this new frontier of wind development was put in condor habitat. We know this because the study of Noel Snyder and Eric Johnson proved it. If you look at the map provided from the study, station 18 was one of the research locations where the condors were photographed. These two researchers also reported that all the condors wereroutinely moving throughout their habitat and were photographed at multiple stations (right). What this means is that the condors were frequently passing over Tehachapi wind turbines as they travelled from the North East area of their range (stations 19, 20 and 21) to the South West area (most other stations).

where the condors were photographed. These two researchers also reported that all the condors wereroutinely moving throughout their habitat and were photographed at multiple stations (right). What this means is that the condors were frequently passing over Tehachapi wind turbines as they travelled from the North East area of their range (stations 19, 20 and 21) to the South West area (most other stations).

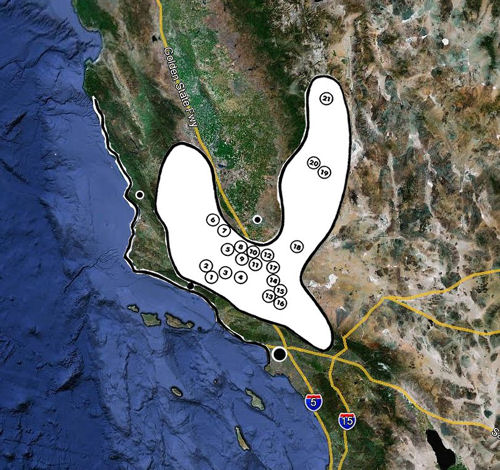

I also took the map from the Snyder, Johnson study and superimposed it on to a Google earth image (left). When I blew up the image where station 18 is located, it was in the middle of a wind development. Even if were not, it is still in the heart of their habitat in the Tehachapi Wind Resource

I also took the map from the Snyder, Johnson study and superimposed it on to a Google earth image (left). When I blew up the image where station 18 is located, it was in the middle of a wind development. Even if were not, it is still in the heart of their habitat in the Tehachapi Wind Resource Area.

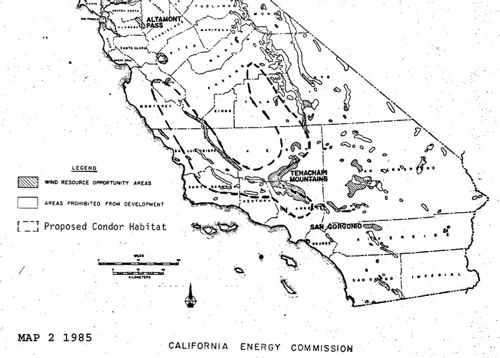

In another development, in April 1985 after the news of the missing condors was revealed, the California Energy Commission (CEC) issued a major statement concerning the condor in a Wind Energy Development in California Status Report P500-85-003.pdf . It was declared that "A major conflict with wind development (primarily in Los Angeles, Ventura, Kern, Tulare, Kings, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, and Monterey counties) is the California Condor. The California Condor is nearly extinct and has been designated as a federal and state endangered species.

"Because condors tend to soar along ridgelines, are large, and not very maneuverable, the primary concern is collisions with wind machines and transmission lines. Condors as well as other birds, are known to fly into tall objects".

"The Condor Research Center (CRC), funded by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the State Department of Fish and Game, and the Audubon Society, has proposed that wind development be curtailed in Condor roosting and foraging habitat. Until more data is available about the bird and until the condor population is increased to a level where it may be possible for it to sustain itself".

"The CRC estimates that it will probably be three to five years before adequate information is available to determine, with any accuracy, if and where developers will be able to construct wind turbines without creating a hazard to the condors."

The report goes on to say that "The problem developers face is that several prime wind development locations are within the known and potential condor range and developers want to be able to take advantage of federal and state tax credits that will expire in 1985 and 1986 respectively(there is a pending proposal to extend the federal tax credits)".

In 1985 the State of California and the CRC declared that collisions with wind turbines were a primary concern and a hazard to the condors. Surprisingly, no other information was given in the report about the many other species at risk or being killed by wind turbine collisions. I want to point out that if anyone is naive enough to believe that the industry would report a dead condor in 1983 or 1984; they must consider an obvious fact about this emerging industry. Billions had already been invested and just one dead condor would have shut down this industry in America. It was an easy choice for greedy investors. Thousands of other dead birds were already being hidden, a few more did not matter.

Since the condors went missing and the CEC 1985 report warning of the wind turbine dangers to condors was published, Kern County has never stopped installing wind turbines. Since 1985 they have allowed wind development to add another 18,000,000 square feet of lethal rotor sweep, they have approved plans for another 35,000,000 square feet, and in the foreseeable future, there are projects that bring nearly another 100,000,000 square feet to Kern county.

When compared to 1982 when there were 21-25 free flying condors, this will be 650 times more rotor sweep with turbines 40 times the size of the early turbines.

Yes, the condors were saved by captive breeding, but their habitat was turned into a mine field by the wind industry. Today the released condors are closely monitored, and if they start to wander into their former habitat, they must be trapped before the turbines get them. There is no doubt some of them will escape the vigilance of the biologists, and get killed. How do you stop a condor from riding the wind?

Part two will cover all the other species being killed by the wind industry, the fraudulent reports, and how the industry with a bogus report, wiped over 50,000 bird fatalities off the books.

Photographic Censusing of the 1982-1983 California Condor Population

Jim Wiegand is an independent wildlife biologist with a degree from the University of California, Berkeley. The views expressed in this editorial reflect the views of its author and do not necessarily reflect the views of East County Magazine. To submit an editorial for consideration, contact editor@eastcountymagazine.org.

wild. The small population of condors was considered to be somewhat stable even though it was severely endangered. Their small numbers had been hanging on for several decades but they were declining. But their exact numbers were in question because their huge foraging territories covered several thousand square miles and researchers weren't sure which birds they were seeing at any given location.

wild. The small population of condors was considered to be somewhat stable even though it was severely endangered. Their small numbers had been hanging on for several decades but they were declining. But their exact numbers were in question because their huge foraging territories covered several thousand square miles and researchers weren't sure which birds they were seeing at any given location.

placed in the condor habitat . By the end of 1985 thousands of new and larger wind turbines had invaded their home, which included the Tehachapi Pass wind resource area. Wind developers had increased their footprint with 19 times more rotor sweep so they could take advantage of expiring tax credits that would end at the of 1985. It would prove be the final blow to the condors.

placed in the condor habitat . By the end of 1985 thousands of new and larger wind turbines had invaded their home, which included the Tehachapi Pass wind resource area. Wind developers had increased their footprint with 19 times more rotor sweep so they could take advantage of expiring tax credits that would end at the of 1985. It would prove be the final blow to the condors.  where the condors were photographed. These two researchers also reported that all the condors wereroutinely moving throughout their habitat and were photographed at multiple stations (right). What this means is that the condors were frequently passing over Tehachapi wind turbines as they travelled from the North East area of their range (stations 19, 20 and 21) to the South West area (most other stations).

where the condors were photographed. These two researchers also reported that all the condors wereroutinely moving throughout their habitat and were photographed at multiple stations (right). What this means is that the condors were frequently passing over Tehachapi wind turbines as they travelled from the North East area of their range (stations 19, 20 and 21) to the South West area (most other stations).  I also took the map from the Snyder, Johnson study and superimposed it on to a Google earth image (left). When I blew up the image where station 18 is located, it was in the middle of a wind development. Even if were not, it is still in the heart of their habitat in the Tehachapi Wind Resource Area.

I also took the map from the Snyder, Johnson study and superimposed it on to a Google earth image (left). When I blew up the image where station 18 is located, it was in the middle of a wind development. Even if were not, it is still in the heart of their habitat in the Tehachapi Wind Resource Area.

Recent comments