By Ron Logan

Caption: On his 49th birthday, Alex contemplates his own mortality, August 3, 2014. Photo by Ron Logan.

August 9, 2014 (San Diego)--He should be dead. Alex Bosworth should be dead. One hospital had already written him off, essentially signing his death warrant. With only six weeks left to live and no chance of survival, he was told to get his affairs in order.

Alex rarely did as he was told.

Two years later I sat across the big wooden table from him. I sipped my Guinness while waiting for my sliders to arrive. He sipped his coffee while waiting for his grilled chicken Caesar salad. He finally had his appetite back. For more than three hours we spoke about his life and near-death experiences.

This is his story.

We met in 1978 at John J. Pershing Junior High School. Back then he was still Brian, but switched to Alex (short form of his middle name, Alexander) to avoid confusion with Brian Bosworth, the football-player-turned-minor-pop-icon. During our first year at Pershing, two of San Diego’s darker events occurred.

On September 25, 1978, Alex and I were in the morning Phys-Ed class. From the sports field we watched as smoke rose in the distance from one of the worst aviation disasters in U.S. history. While on approach, PSA Flight 182 collided in mid-air with a Cessna 172. Both aircraft came to rest in North Park at the corner of Dwight Street and Nile Street. There were no survivors. Seven people on the ground died. 144 fatalities total.

Four months later, on January 29, 1979, Pershing was put on lockdown due to an incident at a neighboring school. I was in class. Alex was not. We all heard the shots.

"The morning of the shooting," said Alex, "I was skipping an 8th grade algebra class with a girl named Melissa in front of the 7-Eleven near San Carlos [Drive] and Lake Murray [Boulevard]. The things you remember. Not the girl’s last name or even whether or not we were frightened, but I remember clearly that I was sharing one of my Mickey’s Banana Dreams in exchange for a gulp of her lime Smiley which I poured into my mouth to show I wasn’t committing backwash. A Coca-Cola delivery guy who also heard the gunshots drove us back to Pershing Junior High in his truck."

Brenda Spencer opened fire on the children and staff of Grover Cleveland Elementary School with her Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic .22 caliber rifle with telescopic sight from the safety of her house across the street from the school, just 1,300 feet away from the 7-Eleven where Alex and Melissa were standing. Spencer killed the principal as he tried to save the children, a janitor while he tried to save the principal, and wounded eight children and a police officer. Her father had given her the rifle and 500 rounds of ammunition for Christmas.

Alex had spoken with Spencer two years before the shootings. "I was walking to little league practice at Cleveland Elementary about a quarter mile from my house. I was eleven and [Spencer] was fifteen. She was an average looking teen in glasses and was sitting near a tree. She seemed a bit sad and vacant. I don’t remember what was said – just sort of a brief acknowledgement.”

Caption: Patrick Henry High School senior portrait from 1983.

Caption: Patrick Henry High School senior portrait from 1983.

Dark days were an exception with Alex. Every time I saw him he was making someone laugh. He was funny, and he was brilliant.

Alex qualified to be a contestant on the game show Jeopardy. His mother, Lillian Bosworth (now Lillian McConnell) was previously a winner on the show. She was a teacher for thirty-five years at Pepper Drive Junior High in Santee. Alex's father, Barry Bosworth, taught at Granite Hills High School for thirty-three years. He developed a successful theatre program, and taught History and English. Both parents were named San Diego County Teachers of the Year – Barry in 1994, and Lillian in 1995.

An aficionado of film, Alex has watched more cinema than my other top ten cinema-watching friends combined. John Wareham, a long-time friend of Alex, recalled, "During his video store days, Brian always said with pride that he had seen every movie in the store." Alex could tell any customer about any movie they brought to the counter. His abilities rivaled those of Rainman.

Ken Thomas, another long-time friend, was also in awe of Alex’s encyclopedic knowledge of film. “Brian and I would spend hours quoting movies back and forth to each other. He had seen everything, it seemed, and he always gave me a hard time when he found out I hadn’t seen the classic movies that I should have.”

In addition to his photographic memory, Alex is a master of improvisation and comic timing. He is comfortable both on stage and in front of the camera.

"I was taking a broadcasting class at a community college,” said Wareham, “and I asked Brian if he was interested in being the host of a one-minute talk show. He said 'sure' and came up to Los Angeles for it. It was multi-camera and since I knew his abilities, I had no script and just let him wing it. He took a few minutes and created his own lines and bits and nailed it four straight times."

Alex got his love of theatrics from his father.

"[Arsenic and Old Lace] is pretty dark and I wanted to see my dad's play," Alex said. "I enjoyed really dark, dark stuff, which started from watching Arsenic. I was six. Dad tells me 'Listen Brian, this is a play. You have to understand this is a play. You're going to see a person in a bag, and a body being moved, and they're going to throw the body and drag it around. Just remember that isn't a real person. That's a freshman who didn't sell all their tickets.'"

Alex's father produced risky shows, created an award-winning drama club, and started an advanced placement college history course at Granite Hills. He expected his students to be punctual and would drop them from his program if their grades started to slip. It was his father’s love of theatre that inspired Alex to pursue a life in the arts. "[Dad] taught me everything I needed to know, theatrically, before I left high school.”

Alex’s early exposure to theatre also sparked his desire to write.

"I started doing bits and routines in school. Class could never start on-time because I'd be in the middle of a bit. Ralph Graves, my fifth grade teacher, asked me 'Have you ever considered writing any of this stuff down? Because it is pretty cool stuff!’”

"Mr. Graves had me read a story [to the class], at least once a week. He would have me write a story, work on it, and have it ready to perform on Friday. Before we went out to the final recess period, I would read them."

"I wrote a story when I was ten that later became a major motion picture,” said Alex. "Of course, nobody knew I had written it. The story was about a moon that had come loose and started flying at the earth from Jupiter, same as the plot of Meteor."

"My first stories were always dark,” Alex said. “Maybe I was influenced by the fact that my dad did The Crucible. My dad had no problem with me seeing The Diary of Anne Frank, The Crucible, Brave New World, or other very dark stuff. I thought they were the most entertaining shows, certainly more than the musicals."

"They had a talent contest at our school [John F. Forward Elementary]," Alex explained. "I did impersonations, which was weird. Ten years old I'm doing Katherine Hepburn, John Wayne, and Howard Cosell. You had to do Howard Cosell. You had to do [Richard] Nixon. I did Ethel Merman. At ten years old I would open my act with Ethel Merman."

Alex joined the Optimists Club in junior high to be in their all-county talent show. He performed an act that he developed in elementary school and made $20 for second place. "I didn't feel bad," said Alex, "because the girl I lost to did 'Jazz Hands.'"

"I tried out for the talent show a couple of times at Patrick Henry [High School] but gave up. The show was run by the band, so non-musical acts were just verboten and my comedy was weird to them."

Although rife with comedy, his life fluctuated between light and dark. In 1978, there was a moment of foreshadowing. Alex was 13 years old.

"I used to spend the summer with my grandfather in Riverside," said Alex. "My grandfather told me to come out to the garage, but to drink some milk first. He took me out to the garage and taught me how to drink [alcohol].”

Caption: Alex reads one of his short stories at Packards Coffee Shop in Ramona, Calif. in September 2011. Photo by Ron Logan.

Caption: Alex reads one of his short stories at Packards Coffee Shop in Ramona, Calif. in September 2011. Photo by Ron Logan.

His grandfather was meticulous with his instruction. "Drink milk first. Never drink on an empty stomach. Coat your stomach. Drink slowly. Sip and take it easy. Never drink good whiskey out out of a coffee mug or a plastic cup. Only use a glass."

"I didn't enjoy it, but I wanted him to think I did. He liked hanging out with me. He wanted me to appreciate something that he really loved, and one of the things he really loved was alcohol.”

"I got drunk for the first time as an adult in Tijuana on my 21st birthday," said Alex. "I hadn’t had so much as a sip of alcohol since I was 13. I went with my friend, Paul Anderson, because he was quite sane and wouldn’t have someone blowing a whistle in my ear and forcing tequila down my throat, nor would he attempt to set me up with a prostitute. It was a respectable night of getting hammered on large margaritas at Tilly’s on Revolución and then staggering back across the border and vomiting on U.S. soil."

Alex began to associate drinking whiskey with two of the best times in his life: the great conversations and bonding he had with his grandfather, and the romantic pursuit of women. "It just became a Pavlovian response,” he said. “And after awhile I really did get to like the taste of whiskey."

"I realized I had a problem about 15 years before I quit," he said. "I realized it when I was thirty. I had been drinking about eight years. Three things happened in a very short period of time which turned me into a heavy drinker: I turned 30, my grandmother died from alcoholism and pancreatic cancer, and my parents' divorce became final. That week I went on a bender, and I mean four or five days straight that I don't remember. I went on a bender, and found that I didn't get sick, I didn't go to the hospital, and it felt pretty good."

Caption: A reading at Lestat's on Park in July 2012. Photo by Ron Logan.

Caption: A reading at Lestat's on Park in July 2012. Photo by Ron Logan.

"I started drinking hard through my thirties and about five years into my forties. I was rarely drunk. I was drinking only bourbon – about a bottle a day – sometimes more. Rarely less. I would start in the morning and go until I crashed in the evening about 14 hours later. I never got a DUI. I never got into a scuffle. I was always under the influence but I was never drunk and never sober, except when I slept."

Alex described his thirties as "Drinking, but not being drunk. Always being buzzed and not drinking during hangovers."

His routine became "Wake up, feel hungover, and take a drink. I would take a couple shots to become normal. It’s a panacea. Boredom. Depression. You need a drink to go to the post office. I had to get a drink to … any time I would leave the apartment I would need a drink. I would need a drink to do my laundry. I always kept two bottles in my car. A brown bottle for me, and a white bottle for someone else. I drank bourbon and most other people drank vodka. Vodka mixes with everything."

"I saw it coming a long way away," he said. "I knew it would eventually kill me. I took it for granted that it would kill me. I lost my spleen when I was nine years old. It is one of the filters of the blood. I had one less filter to filter my blood [from alcohol]."

Alex's family didn’t grasp the severity of the disease, but his brother Bruce experienced it first-hand while on a trip to The Happiest Place on Earth, Disneyland.

“Bruce had no idea how bad it was. I went into the men's restroom and knocked a couple of mini bottles back. He asked me if I wanted to go on a roller coaster and I said, 'No, you guys go ahead," and he told me I was yellow. I said 'Hey, I don't like roller coasters!’ I literally didn't know what he meant. But he said, 'no, you're yellow. Your skin is yellow. Your eyes are yellow.'"

At the age of 43, Alex was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver.

Caption: Alex during one of his many hospital stays in December 2012. Photo by Traci Lopez-Bosworth.

Caption: Alex during one of his many hospital stays in December 2012. Photo by Traci Lopez-Bosworth.

"The problem is I went to that building right there [a local area hospital]," Alex said. "I went in with my father. I asked, 'Dad, will you take me to the hospital? I need to go to rehab.' I needed a doctor to refer me in order to go to rehab. I said, 'Go with me. I need some support,' and we went to the hospital. We thought it was a great hospital. I chose it out of loyalty. I was born there. But it was bought up by a for-profit corporation."

"We went. They said I had to go to the E.R. – my dad was afraid to break the rules. I go in there and the guy is not interested in me at all. I had had a couple drinks before I went and I think that turned him off. He was young."

"I wanted to see if it was depression, or alcoholism, or both,” said Alex. “I wanted to be under a doctor's supervision. I didn't know if they would dry me out or put me on medication or what. I wanted to get into Mesa Vista [Hospital]. But the guy at the local hospital tested my blood and put me in the E.R. He said I didn't really need to be there. I told him I wanted to go to rehab and he told me 'I don't think rehab works.' So I couldn't go to rehab, and that was five years before I quit. How much damage did five years of drinking a bottle of whiskey a day do? He told me to go to A.A. [Alcoholics Anonymous] and to get my affairs in order, then released me. Based on his personal opinion, I didn't need rehab. I was uninsured and they didn't care about me."

“A year later, after several trips to multiple hospitals for various health problems, I collapsed with double pneumonia and kidney failure and was intubated for ten days,” Alex explained. “The kidney specialists there told my wife and family I would not survive. My brother, who is not a doctor, asked if they had tried dialysis. They said no, but they’d do it, if it would make him feel better. The day after they hooked me up [to dialysis], I recovered."

“A few days later, a doctor visiting from another hospital told me in confidence that a corporate hospital was never going to help me because I was uninsured. He suggested I should get out of there and get admitted to a college hospital.”

Caption: The cover of Alex Bosworth's published book.

Caption: The cover of Alex Bosworth's published book.

When not in the hospital, Alex performed monthly readings at local coffeehouses. He read at New Poetic Brew at Rebecca’s in South Park and at Dime Stories at Lestat’s on Park in University Heights. “I did perform between hospital stays, when I was deathly ill and there was nothing specific they could do for me,” Alex said. “And I was rushed to UCSD in Hillcrest straight after I read at the new Lestat's once.”

One of Alex’s fellow writers took note of his clever storytelling. Jill Badonsky, author, illustrator and owner of Renegade Muses Publishing House, explained, “I would hear Alex read his stories and think to myself ‘Surely he is published somewhere and I want to read his book because he ranks up there among favorite authors like David Sedaris and Miranda July,’” she said. “I asked him where I could GET his book and he said he wasn’t published. I was flummoxed – mainly because I’m a writer too – if I wasn’t a writer I’d be ‘baffled’ or just ‘surprised.’”

As Alex’s health rapidly declined he pushed to finish his first book, a collection of humorous short stories titled Chip Chip Chaw: Tales of the Unsane. His book garnered positive reader reviews, including: “I DO remember spewing latte out of my nose reading a story that was only a page and a half long. I laughed, really laughed, and I really wasn't expecting to,” and this, "Each story is written with originality and creative genius. I can't wait to see more from this author."

Alex completed his book, I did the cover art for him, and Badonsky had it published while he was lying in a hospital bed. “I took some of my inheritance and published his short stories myself,” she said. “Not to make money, but because it was a crime that his stories weren’t already out there for everyone to read. Now they are.”

Caption: Drinking a non-alcoholic beverage in his hachimaki in August 2013. Photo by Traci Lopez-Bosworth.

Caption: Drinking a non-alcoholic beverage in his hachimaki in August 2013. Photo by Traci Lopez-Bosworth.

"Most of my stories are written from the 'first person idiot' point of view," Alex noted. "A lot of my stories are what my audience knows about, but I as the storyteller, am not very bright about it." His short story about Elvis’ shirt used this technique.

“The Shroud of Memphis was based on my grandmother," Alex said. “She believed very heavily on a little splinter she kept with her. She bought it from an ad in the back of a comic book. She kept it in a little plastic case around her neck and believed it was a real piece of The Cross."

Caption: An X-ray taken at UCSD Medical Center La Jolla showing the results of his cervical laminectomy. Photo courtesy of Alex Bosworth.

Caption: An X-ray taken at UCSD Medical Center La Jolla showing the results of his cervical laminectomy. Photo courtesy of Alex Bosworth.

I remember speaking with Alex about Chip Chip Chaw while visiting him in the hospital. I wore a plastic medical gown, a face mask, and medical gloves to protect him from outside contaminants. He was thin, gaunt, and frail. His hands burned constantly from an unrelated condition, spinal stenosis, which caused a narrowing of his spine (he later underwent a cervical laminectomy to help alleviate the condition). He was heavily sedated. Bed-ridden. Uncomfortable. “What was the French Revolution, Alex?” Jeopardy. Every night. He always answered before the contestants.

"So, this doctor had told me I needed to get on a liver transplant list or I was going to die," said Alex. "I had been told I had six weeks to live and that they wouldn't put me on a transplant list because they didn't think I'd make it long enough to find a donor. It might take six months to find a donor. And I was an alcoholic. But that doctor told me that UCSD [Medical Center] Hillcrest is the place to get this done. 'You didn't hear this from me,' the doctor said, 'but you need to get to UCSD Medical Center in La Jolla or Hillcrest and get a liver replacement team.'"

“The local hospital released me," said Alex, "and I asked my dad if he wanted to go to La Jolla to relax. Dad likes to park above the Cove and stare out at the water. When we were out there I told my dad I needed to get my oxygen tank refilled and asked if we could stop by UCSD Medical Center on the way home."

Caption: One of the Blue Man Group with Alex in Las Vegas in June 2014. Photo by Traci Lopez-Bosworth.

Caption: One of the Blue Man Group with Alex in Las Vegas in June 2014. Photo by Traci Lopez-Bosworth.

Alex did not, in fact, need his tank refilled. He lied. It was three-quarters full and contained more than enough oxygen to get him back home safely. But Alex knew he was dying and that unless he received appropriate care he had very little time left. So he lied to his father and to the E.R. nurse. A small lie. A white lie. An exaggeration, really.

That lie saved his life.

"We went to the E.R. and we got right in as it was a Tuesday afternoon," Alex explained. "I told the nurse I was running out of oxygen. She asked if I was okay and checked my fingertips which were blue. I had been released from that other hospital only 90 minutes before and nobody had looked at my fingertips."

The nurse told Alex, "You need a liver transplant. When did they put you on a list?" "I'm not on a list," Alex replied. "Well, we're gonna get you on a list," she said. "You have very little time. Are you insured? You're not? Okay. We need to get you on Medicare. As soon as you get covered we'll get you down to [UCSD Medical Center in] Hillcrest." The nurse helped Alex complete the Medicare application paperwork.

When Alex applied to be put on the waiting list for a donor liver, he signed a contract agreeing to abstain from illegal drugs and alcohol and that he would attend A.A. regularly. He finally quit drinking. “I’m pretty sure my last drink was a double bourbon at The Silver Fox Lounge in Pacific Beach some time in December of 2010,” he said.

"I had been to that other hospital for two or three years with nothing,” said Alex. "Because I was a liability. I had no insurance. So I lied my way in [to UCSD Medical Center]. All I had to do was lie about my oxygen running out and they took care of the rest. UCSD took me in. They got me on Medicare. They made me a case study. They gave me a liver transplant and they are trying out new anti-rejection drugs. They saved my life.”

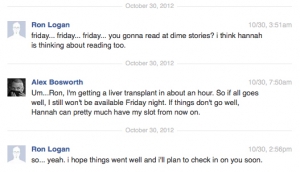

All this time I had been following Alex’s progress on Facebook. On October 30, 2012, I wrote him a personal message that read: “friday… friday… friday… you gonna read at dime stories? i think hannah [my girlfriend] is thinking of reading too.” Alex responded, “Um… Ron, I’m getting a liver transplant in about an hour. So if all goes well, I still won’t be available Friday night. If things don’t go well, Hannah can pretty much have my slot from now on.” By the time I read that response the following day he was already in recovery with his new liver.

Caption: Our October 30, 2012 Facebook messages.

Caption: Our October 30, 2012 Facebook messages.

So, Alex was given a second chance. He looks healthy again. He feels well. He is working on his next book. He continues to perform at coffeehouses and will continue to share his wit and wisdom with all who listen to, or read, his words. If you get the chance, check him out. His life play is one of the best in East County, and it just got extended.

—————————

Alex can be seen regularly performing at local coffeehouses. On the second Friday of each month, he reads at Dime Stories ( www.sandiegowriters.org/new-location-dimestories-open-mic/ ), which is now at Liberty Station, Barracks 16. On the third Tuesday, I read at Poetic Brew ( https://www.facebook.com/pages/New-Poetic-Brew/287925501718 ) which is held at Rebecca's in South Park.

Alex’s reading of his short story Moths on the Moon on the UCSD Campus can be heard here: http://youtu.be/Y0EaJNlQImc

Chip Chip Chaw: Tales of the Unsane is currently available on Amazon. www.amazon.com/Chip-Chaw-Alex-Bosworth/dp/0985464674/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&...

Recent comments