New York declares statewide emergency after wastewater testing repeatedly finds polio in four counties; man left paralyzed

By Dr. Henri Migala

Photo: Iron lung machines in Downey, CA circa 1953, U.S. FDA

September 22, 2022 (San Diego) -- San Diego County funds wastewater testing in our region for COVID-19 and, more recently, for Monkeypox. But so far, no testing for polio has been authorized locally-- despite a resurgence in the U.S. of polio, the Governor of New York declaring a ‘state of emergency after the detection of polio in multiple counties, paralysis of one patient, and a directive this week from the Centers for Disease Control urging wastewater testing in at-risk communities.

The dreaded disease that once paralyzed 1,000 children each day has been eradicated in the US for nearly half a century. The disease spreads in an insidious way, with the vast majority of polio cases being without any symptoms. Scientific studies indicate that only 1 in 200 infections, with some studies stating 1 in 2,000 infections, result in paralysis. Mild cases most often have only flu-like symptoms. As a result, polio can be present and spreading in a community, with hundreds of people being infected and infecting others, long before a case is detected in a clinic. Without the appropriate surveillance, the potential for polio now silently spreading beyond New York is a very real threat.

San Diego is an international hub for travelers, many of whom have come through airports in New York and cities overseas that have also recently detected the polio virus, such as London and Jerusalem. Our region is also a primary resettlement area for people from around the world, including from areas where the wild polio virus is still endemic, including Afghanistan; many Afghan refugees have settled in East County Additionally, American service members deployed from military bases here have served in countries where polio is still circulating.

So, why aren’t County health officials taking steps to proactively test for the polio virus in wastewater, a standard practice in many countries? The County already contracts with SEARCH (San Diego Epidemiology and Research for COVID Health) to test wastewater for COVID-19 and Monkeypox, to assure the earliest possible detection of any outbreak in our region. This testing is done at the Point Loma wastewater treatment facility, which handles wastewater from all four East County cities as well as San Diego and most other parts of the county.

Polio is back in the US -- and it's spreading

For only the second time in 43 years, a case of paralytic polio has been detected in the US. More alarmingly, polio has been continually detected in wastewater in several New York counties and might well be detected elsewhere, if testing were being done.

New York State Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state of emergency following the recent identification of a young man who developed paralysis from polio and the ongoing detection of the polio virus in wastewater samples every month from May through August from New York City and multiple counties surrounding the metropolitan area.

The single case of paralytic polio was identified in a young unvaccinated man living in Rockland County, north of New York City, on July 21. The New York State Department of Health said the man had contracted the virus through local transmission, which means he had not travelled outside the US. He said he attended a large public event in the preceding eight days before he started noticing symptoms.

The emergency order releases more state funds to combat the spread of the disease and authorizes emergency medical service workers, midwives, and pharmacists to administer polio vaccines to the public.

Working with the UN WHO in the Global Polio Eradication Program

With a background in medical anthropology and international public health, I had an opportunity to work with the United Nations (UN) World Health Organization Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 2000. At the time, the epicenter of the global polio epidemic was in India, in the two small states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (“UP”), together, about the size of Louisiana but with a combined population larger than that of the entire United States.

Photo, right, b y Dr. Henri Migala: United Nation's World Health Organization has led efforts to eradicate polio.

y Dr. Henri Migala: United Nation's World Health Organization has led efforts to eradicate polio.

At the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, we were trained by the world’s experts on polio, disease eradication, epidemiology, social mobilization, and surveillance. Then we were assigned to work under the UN World Health Organization while deployed in the field. This was done to provide international and political immunity and neutrality to vaccination workers in all nations, especially those where political relations are sensitive or conflict was present.

We were given our choice of countries and I chose Nepal. My mission was to help prepare the country for a national immunization program to immunize five million children in three days along the entire border with India to prevent the polio virus that was circulating in India from reentering Nepal.

Photo, left: Dr. Henri MIgala with children in Nepal during efforts to vaccinate the population.

Why test wastewater?

Wastewater is tested for polio virus in at-risk areas because the virus is shed through feces (poop) and because of the low incidence of symptoms associated with polio infection. Since only 1 in every 200 to 2,000 infections result in paralysis, hundreds of people in a community can be infected with polio, even if they are immunized, shedding and spreading the virus and infecting others, without any clinical indication that the virus is present in the community.

Testing wastewater for the polio virus is an efficient, effective and prudent way to test for the presence of polio in a region. It allows authorities to identify the presence of the polio virus and take appropriate preventive measure before any case of paralysis is presented or identified in a clinic or hospital.

Water Treatment in San Diego

East County Magazine sought to find out if San Diego is testing its wastewater for polio as part of the county’s surveillance efforts to protect the public from communicable diseases. Given the risk factors here in our region, it would seem reasonable and prudent for the Department of Health and Human Services to test San Diego wastewater for polio virus, especially now that that the CDC recommends doing so.

East County Magazine contacted various county agencies, water authorities, wastewater training programs, and elected officials to find out what efforts are being undertaken to surveil for polio in San Diego, why polio is not included in the pathogens currently being tested for in wastewater, who makes the decision to add polio to the pathogens currently being tested in our wastewater, and what it would take to add polio to the pathogens currently being tested for in wastewater.

Wastewater surveillance in San Diego is conducted by SEARCH, a consortium of scientists from UC San Diego, Scripps Research and Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, working with San Diego County public health officials and others.

Testing wastewater for polio has been discussed by members of SEARCH but authorities have not provided answers as to why polio was not added for testing, nor answers to many of ECM’s other questions.

“Scripps/SEARCH isn’t currently working on polio,” responded Kristina Grifantini, Director, Scientific Communications and Marketing at Scripps Research, to inquiries about testing wastewater for polio.

Follow-up questions to Grifantini included:

Follow-up questions to Grifantini included:

- Why did SEARCH, after discussing testing wastewater for polio, decide not to do so?

- What would it take for SEARCH to add polio to what it's testing in wastewater?

- What would the budget be for testing wastewater for polio?

These questions merely resulted in a recommendation that ECM try “reaching out to the County; they should be able to help with these questions.”

Inquires to the County of San Diego, Department of Public Works, Wastewater Management, about testing county wastewater for polio received only this response: “The County does not test for pathogens,” Mike Bedard advised. This is a surprising and puzzling response because the county has been collaborating with SEARCH to test wastewater for COVID-19 since May and has recently added Monkeypox.

The San Diego County Water Authority directed ECM to the Padre Dam Municipal Water District website and to the San Diego County’s Climate Action Plan website. Neither had information about testing wastewater.

The Padre Dam Municipal Water District’s Director of Operations and Water Quality confirmed that “the District does not currently test for water systems for polio,” Melissa McChesney, Communications Manager, Padre Dam Municipal Water District.

An email to the County of San Diego Public Utilities, Sewer Treatment, was unanswered.

The California Department of Water Resources provided a phone number to Groundwater, but calls to the number resulted in a busy signal for a few seconds and then the line is disconnected. The agency also provided a phone number to Conservation, but the call is answered by an automated system that states that “the mailbox is full and cannot take messages,” and then the line is disconnected.

ECM also reached out to Michael Botello, Director of Communications for Supervisor Joel Anderson. Botello responded that he would find the appropriate people and forward my inquires to them, which he did.

The most helpful contact was Mike Uhrhammer, Senior Public Affairs Representative for the Helix Water District. Uhrhammer was very informative in helping ECM find additional information related to wastewater in San Diego, such as contacts with SEARCH members, and providing maps, graphics, articles and links to and about San Diego’s wastewater treatment and testing.

Tim McCain, Public Affairs Coordinator, San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services. McCain was very helpful in helping ECM understand the policies and regulations related to the immunization status of refugees, but questions related to wastewater were unanswered.

Vaccines and Coverage in the US

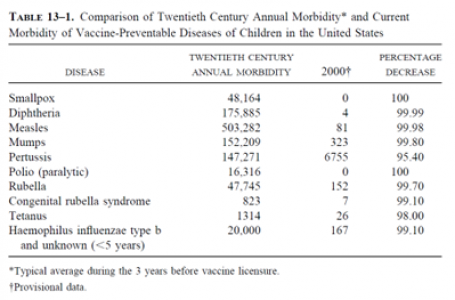

The beginning of the vaccine era can be traced back to 1786, when Edward Jenner used matter from open cowpox lesions to inoculate patients to protect them from smallpox.  It was nearly 100 years until the next vaccine (against rabies) was introduced. Throughout the 1900s, many new vaccines were developed and used, with great success to protect the population from disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared vaccinations to be one of the 10 great public health achievements of the twentieth century.

It was nearly 100 years until the next vaccine (against rabies) was introduced. Throughout the 1900s, many new vaccines were developed and used, with great success to protect the population from disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared vaccinations to be one of the 10 great public health achievements of the twentieth century.

Although the most recent CDC data shows almost 94% of kindergarten-age students in the U.S. received the polio vaccine for the 2020-2021 school year, rates vary by state.

Although the most recent CDC data shows almost 94% of kindergarten-age students in the U.S. received the polio vaccine for the 2020-2021 school year, rates vary by state.

The states with the highest vaccination rates against polio include Mississippi with 98.9% of kindergartners vaccinated against polio. The other top states with the highest vaccination rates include Louisiana; New York, excluding New York City; Nebraska; and Rhode Island.

Among the states with the lowest rates of polio vaccination include Washington, D.C., which had the lowest rate at just 80.4%, Idaho (86.6%), Wisconsin, Hawaii and Georgia -- all with rates under 90%.

In New York, where the current polio outbreak is taking place, the statewide average for vaccination against polio is only 78.96, under the required 80% which is needed to ensure “herd immunity,” which is the minimum level of immunization required in a population to protect from a disease becoming a widespread epidemic.

The four counties where the polio virus has been detected in the wastewater have some of the lowest polio vaccination rates in the states with Rockland at 60.34%, Nassau 79.15%, Orange 58.68%, and Sullivan County at 62.33%, and one zip code having only 39% vaccinated. Statistics for the New York metropolitan areas were not available from the New York State Department of Health website.

Vaccination status of immigrants and refugees arriving in San Diego

San Diego has long been the site where refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants are settled. Initially from Vietnam, then from various other countries in conflict around world, such as Iraq, Syria, Congo, and others, and now, most recently, from Afghanistan. Afghanistan and Pakistan are the only two countries left in the world where the wild polio virus is still endemic (is still naturally part of the local ecology and environment).

ECM reached out to the County’s Office of Immigrant and Refugee Affairs to find out about the vaccination status and requirements of refugees being resettled in San Diego.

Lenda Hanna, an Administrative Analyst with the office’s Department of Homeless Solutions & Equitable Communities, responded, “I forwarded your email to the proper department and someone from the Agency Executive Office will respond to you.” No one responded, however ECM tracked down the information elsewhere.

According to Tim McClain, Public Affairs Coordinator with the San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services, “all applicants for immigrant visas are generally required to received one dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) within 12 months before traveling to the U.S. if they are residents or long-term visitors from countries infected with polio and new variants, to prevent international spread.”

According to Tim McClain, Public Affairs Coordinator with the San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services, “all applicants for immigrant visas are generally required to received one dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) within 12 months before traveling to the U.S. if they are residents or long-term visitors from countries infected with polio and new variants, to prevent international spread.”

“Those applying for US Refugee or Visa 92 or 93 status are not required to receive vaccinations before travel to the US.” Continued McCain. “However, they may receive overseas vaccinations through the Vaccination Program for US-bound Refugees. Additionally, some may be required to meet other vaccination requirements separate from the immigration medical exam. Children who received the oral polio vaccine in April 2016 or later should be revaccinated with the inactive polio vaccine.”

According to McCain, “the U.S. government continues to take every precaution to stop the spread of diseases, consistent with Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidance. All arrivals – U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents, and Afghan nationals –have the option to receive COVID-19 and other vaccines either at U.S. government-run sites near Washington Dulles International Airport and Philadelphia International Airport, or at a Department of Defense facility. All testing, vaccinations, and other services are available at no cost.”

Afghan refugees admitted to the U.S. are required to undergo medical screening and receive the first dose of these the following vaccines (unless not medically appropriate, such as with an allergy):

- Polio vaccination, absent proof of prior vaccination

- COVID-19 vaccination, absent proof of prior vaccination

- MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccination, absent proof of prior vaccination

- Other age-appropriate vaccinations, as determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- A tuberculosis screening; it will be required to take appropriate isolation and treatment measures if the tuberculosis test is positive

What is Polio?

Information about symptoms, transmission, prevention, diagnosis and treatment can be found on the CDC website:

https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/index.htm

According to the CDC, most people who get infected with poliovirus will not have any visible symptoms. About 1 out of 4 will have flu-like symptoms that can include sore throat, fever, fatigue, nausea, headache or stomach pain that lasts around 2 to 5 days, then goes away.

A small proportion will develop other, more serious symptoms that affect the brain and spinal cord, including meningitis or paralysis. “Poliomyelitis” (or “polio” for short) is defined as the paralytic disease. So only people with the paralytic infection are considered to have the disease.

But even children who seem to fully recover can develop new muscle pain, weakness, or paralysis as adults, 15 to 40 years later. This is called post-polio syndrome.

Paralysis

Polio can leave you permanently unable to move parts of your body. It most commonly paralyzes the legs. In severe cases, polio can paralyze the muscles you use to breathe or swallow. This can cause death.

Photo, right, by Dr. Henri Migala: A child in Nepal is examined for polio paralysis

Paralytic polio causes what is known as acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). Flaccid means soft, limp and lifeless. It is not a rigid paralysis, causing stiffness. The limb is just there, limp, and unresponsive.

Acute means the paralysis can happen in a matter of hours. When finding a case of suspected polio, it is not uncommon to hear a distraught mother say her child was “fine yesterday, playing and running. But when she woke up this morning, she couldn’t move her leg.”

Paralysis that comes with polio results in the lack of any ability to move one or more arms or legs. All sensation is still there. What is missing and gone forever is the ability to move the limb(s).

Recent Polio Case in the U.S. and Vaccination rates

Nationwide, the polio v accination rate is about 93%. Polio was declared eradicated in the US in 1979, and the entire western hemisphere was certified ‘polio free’ in 1994.

accination rate is about 93%. Polio was declared eradicated in the US in 1979, and the entire western hemisphere was certified ‘polio free’ in 1994.

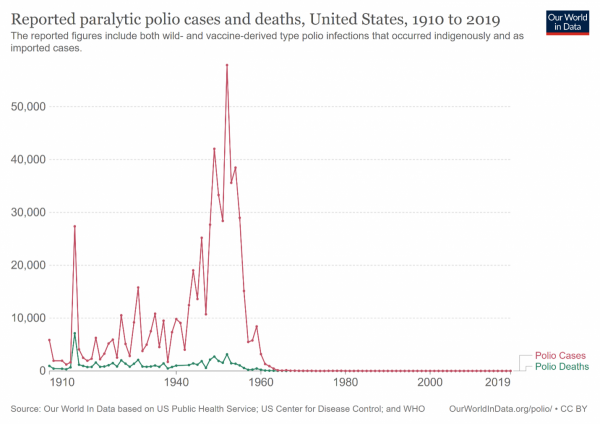

In the early decades of the 20th century, polio was once a widely feared illness, affecting and paralyzing more than 35,000 people in the U.S. each year -- 1,000 per day, in the 1940s.

After development and introduction of the polio vaccine by Dr. Jonas Salk in 1955, the number of cases dramatically dropped in the United States. The last case of wild polio in the US was found in 1979. In recent months, however, this has changed with the detection of paralytic polio in an unvaccinated male in New York on July 18 and the ongoing detection of polio virus in wastewater in multiple counties in the state.

The patient was unvaccinated and experts believe he contracted it from someone who had received the oral polio vaccine, which can, on rare occasions, mutate back into a paralytic form. The oral vaccine is no longer used in the United State, since the injected version is far safer.

There are two types of vaccine that can prevent polio: the injectable dead vaccine used in the US, and the oral live, or “attenuated,” vaccine used in lesser-developed countries.

Inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) is given as an injection in the leg or arm, depending on the patient’s age. Only IPV has been used in the United States since 2000. It is extremely safe and cannot cause polio.CDC and the California Department of Public Health recommend that children get four doses of polio vaccine. They should get one dose at each of the following ages: 2 months old, 4 months old, 6 through 18 months old, and 4 through 6 years old.

Oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) is still used throughout much of the developing world. This oral vaccine contains a weakened “attenuated” strain of the virus that causes polio.

Oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) is still used throughout much of the developing world. This oral vaccine contains a weakened “attenuated” strain of the virus that causes polio.

Photo, right, by Dr. Henri Migala: Oral polio vaccine is administered to a child.

On very rare occasions, 1 in 3,000,000, this strain can change over time and start to behave similarly to a wild-type polio infection — spreading easily among people who are not vaccinated and causing illness, including paralysis. The oral vaccine is used in other, lesser developed countries where the lack of infrastructure prevents the distribution, use and recovery of millions of syringes, and the thousands of trained medical personnel needed to administer a vaccine with a syringe are not available.

The unvaccinated New York resident who contracted paralytic polio recently was infected by someone who was administered the oral vaccine in his/her country then came to the US.

The injectable polio vaccine used in the U.S. is very safe and protects against both wild polio and the weakened oral vaccine-derived strain.

Of great concern is that where the recent polio virus has been detected in the wastewater of multiple counties in New York, the vaccination rates are some of the lowest in the state, well below the required 80% needed to ensure ‘herd immunity,’ a minimal level of immunization in a community to protect from widespread infection. In one New York zip code, the immunization rate against polio is only 37%.

The ongoing detection of polio in the wastewater of four New York Counties resulted in the Governor declaring a state disaster emergency on September 9, 2022, which increases the availability of resources to protect people in the state.

The ongoing detection of polio in the wastewater of four New York Counties resulted in the Governor declaring a state disaster emergency on September 9, 2022, which increases the availability of resources to protect people in the state.

Global Eradication nearly succeeded

Rotary International launched “Polio Plus,” a global effort to immunize the world’s children against polio in 1985. Rotary had an initial goal of raising $120 million to support the effort, but during its convention in 1988, in Philadelphia, Rotary announces it had raised $247 million, more than double the target amount.

In 1988, when polio paralyzed about 1,000 people every day worldwide and the virus was circulating in 125 countries, and with the financial backing of Rotary International, the World Health Assembly launched an ambitious global campaign to eradicate polio by 2000. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) is a joint effort between the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Rotary International, US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and national governments.

The partnership achieved phenomenal success: global incidents fell from over 350,000 cases in 1988 to only five cases of wild polio in 2021, and only four so far in 2022. The number of countries where the wild polio virus is still circulating has dropped from the original 125 to only two: Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The World Health Assembly chose to take on eradiating polio because of the relatively “easy” process. There are no animal vectors (carriers), including insects, of the disease. Transmission is only from person-person. An infected person is not infectious for very long, no more than only 3-6 weeks. Once shed, the virus doesn’t last long in the environment, and we have very effective and easy to administer vaccines.

Global Setbacks

The world community was steadily progressing towards total eradication of polio until global political events, specifically, the attack on the World Trade Centers in New York on 9/11 and the subsequent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq by the United States, and the hunt for bin Laden, changed everything.

The target to rid the world of polio came under threat when Muslim religious and political leaders in northern Nigeria brought the polio immunization drive to a standstill, in response to fears that the vaccines were deliberately contaminated with anti-fertility agents and the HIV virus, a general distrust of the West following the US invasion of Iraq, and the use of a sham vaccination campaign in Afghanistan used by intelligence agencies in an effort to track Osama bin Laden.

The target to rid the world of polio came under threat when Muslim religious and political leaders in northern Nigeria brought the polio immunization drive to a standstill, in response to fears that the vaccines were deliberately contaminated with anti-fertility agents and the HIV virus, a general distrust of the West following the US invasion of Iraq, and the use of a sham vaccination campaign in Afghanistan used by intelligence agencies in an effort to track Osama bin Laden.

Nigeria

In northern Nigeria in 2003, the political and religious leaders of Kano, Zamfara, and Kaduna states brought the immunization campaign to a halt by calling on parents not to allow their children to be immunized. These leaders argued that the vaccine could be contaminated with anti-fertility agents (estradiol hormone), HIV, and cancerous agents, according to an article titled “What Led to the Nigerian Boycott of the Polio Vaccination Campaign?” published by the National Institute of Health on its National Library of Medicine. . This was a claim that I also heard during my work in Nepal in Muslim communities.

According to the article, the New York Sun reported that this fear of polio vaccines in northern Nigeria “caught on because of the war in Iraq”. Ali Guda Takai, a WHO doctor investigating polio cases in Kano, told the Baltimore Sun, “What is happening in the Middle East has aggravated the situation. If America is fighting people in the Middle East, the conclusion is that they are fighting Muslims.”

Vaccinations were allowed to start only after religious leaders from Nigeria agreed to have labs in “Muslim countries” (South Africa, Indonesia, India) test the polio vaccine to prove it was not contaminated with HIV. The sample tests came back negative and the polio immunization campaign was restarted.

The 11-month boycott against polio vaccines proved a huge setback for polio eradication globally. Incidents in Nigeria jumped from 202 in 2002 to 1,143 in 2006. During those 11 months, Muslims from around the world, including Nigeria, participated in the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, in Saudi Arabia. With millions of people crowding into Mecca, the polio virus spread easily and was carried back by pilgrims throughout Africa and the world again.

Afghanistan

Following the attack on the World Trade Center on 9/11, the US was determined to get Osama bin Laden. During the Obama administration, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) organized a fake vaccination program in Abbottabad, the town where it believed Osama bin Laden was hiding, in an elaborate attempt to obtain DNA from one of bin Laden’s family members so it could be matched with DNA obtained from bin Laden’s sister, who died in 2010 in Boston.

The effort failed, but once the operation was detected, the violation of trust threatened the lives of public health workers around the world and set back global public health efforts by decades. Dozens of immunization workers in Pakistan, Afghanistan and other countries were killed. Most recently, on February 24, 2022, the World Health Organization condemned the brutal killing of eight polio workers, four of them women, in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan planned to vaccinate 10 million children under five across the country, but as a result of the killings, the UN immediately suspended the national polio vaccination campaign in Kunduz and Takhar provinces, leaving thousands of children vulnerable to infection from polio.

Final Eradication of wild polio is near

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) recently released its Global Polio Eradication Strategy 2022-2026, which lays out the plan for identifying the last case of wild polio by the end of 2023, which would allow the WHO to certify the entire world free of polio by the end of 2026. It takes three years of no detection of paralytic polio to obtain an official designation of being ‘polio free.

To date, the world is very close. Only two countries in the world still have wild polio, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Now that the conflict is over in Afghanistan and the Taliban is in control of the entire country, they have taken on the responsibility of organizing and implementing polio vaccination campaigns. As a result, Afghanistan has detected only three cases of paralytic polio, and Pakistan only one, in 2022. But as the recent brutal killings of polio workers demonstrates, challenges still exist in some of the more isolated areas.

Protect San Diego

The World Health Organization divides the world into six regions, and the U.S. is in the Pan American Health Organ ization (PAHO). The last case of paralytic polio caused by the wild virus in the US was in 1979, and PAHO was the first region in the world to be certified as ‘polio free’ by the World Health Organization in 1994. Ironically, in 2022, polio is back in the US.

ization (PAHO). The last case of paralytic polio caused by the wild virus in the US was in 1979, and PAHO was the first region in the world to be certified as ‘polio free’ by the World Health Organization in 1994. Ironically, in 2022, polio is back in the US.

With the recent detection of the polio virus in Jerusalem, London and now New York, the long fight to eradicate polio is close, but clearly not over. San Diego is one of the Top 10 destination cities in the US, receiving 35 million visitors each year. Additionally, our large military community sends service members to countries where polio is still a concern, and California follows only Texas as the state receiving the most Afghan refugees (Afghanistan being one of only two countries where wild polio is still present).

It would seem that testing the wastewater for polio, something San Diego is already doing with COVID-19 and Monkeypox, would be a wise and prudent precaution to detect the circulation of polio in San Diego and protect our residents – before a child needlessly loses his/her ability to walk for the rest of his/her life, or worse.

Dr. Henri Migala has won numerous journalism and photography awards including honors from Society of Professional Journalism and San Diego Press Club for reporting with East County Magazine on COVID-19, civil unrest, and social justice issues.

Dr. Henri Migala has won numerous journalism and photography awards including honors from Society of Professional Journalism and San Diego Press Club for reporting with East County Magazine on COVID-19, civil unrest, and social justice issues.

He holds a doctor of education degree from San Diego State university, a Masters in Public Health from the University of North Texas, and a Master of Art degree at the University of Texas, where he studied anthropology. Dr. Migala has lived and worked in 15 countries in global health, international development, higher education administration and humanitarian aid including disaster relief.

His past positions include Director of International House at the University of California San Diego, Executive Dean and Grants Administrator for Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community College District, and Adjunct Faculty instructor at San Diego City College. Dr. Migala has published numerous academic papers and written nearly $30 million in grants that have been funded.

As a Rotary Club President, he has worked with International Relief Teams. He speaks three languages (English, Spanish and French) and has won many awards for community service and international activities include working to eradicate polio through the World Health Organization, as well as participating in rural, border and cross-cultural health issues, disaster relief and reconstruction. A volunteer and board member with Aguilas del Desierto, Inc., he also helps save the lives of lost migrants and is the founder of Henri Migala Photography.

Recent comments