San Diego has sixth highest rate of valley fever in California; concerns voiced that Imperial County cases may be under-reported

By Janice Arenofsky

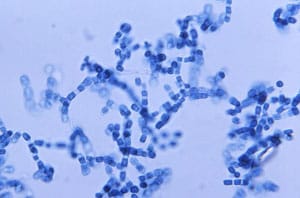

July 13, 2014 (San Diego)--More than 160 scientists, researchers and regional activists met in Phoenix on April 5th to learn about and exchange views on the human and economic costs of Coccidioidomycosis (valley fever). Due to recent national and local media coverage of the valley fever epidemic across the Southwest and formation of a Cocci Congressional Task Force headed by two U.S. House Republicans from California and Arizona-- Kevin McCarthy and David Schweikert--the 58th Annual Meeting of the Cocci Study Group brought together a historic number of attendees.

Keynote speaker Steven Holland, MD, deputy director for intramural clinical research at the National Institutes of Health, spoke about human DNA mutations that leave a percentage of people especially vulnerable to valley fever, mycobacterial disease and Job’s Syndrome (immune-mediated disease). Holland concluded that in certain extreme cases of cocci, bone marrow transplants should be considered. He anticipates receiving more referrals of seriously ill cocci patients from Arizona and California physicians.

Because immune-compromised people are vulnerable to developing serious illness, Texas researchers are working on a cocci vaccine project headed by Garry T. Cole, MD, at the University of Texas, San Antonio. The authors of a paper confirming the necessity of Th17 immunity for protection against valley fever informed attendees that a successful vaccine would have to provide for this.

Although vaccine research is ongoing in both Arizona and Texas, pharmaceutical companies do not yet underwrite it since they consider the market relatively small (only 150,000 valley fever cases are documented each year and cocci is an orphan disease).

Furthermore, despite positive laboratory results at the University of Arizona, Tucson, which showed tweaking a cocci gene yielded a disease-resistant strain producing immunity in mice, the FDA is hesitant to back a live attenuated vaccine (not a killed virus) for clinical trials. However, John Galgiani, MD, director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence in Tucson, says another option the Center is considering is licensing this research to a veterinary facility for use in dogs and other animals. Then, perhaps, the private sector would apply pressure and raise support for a human vaccine.

Actually, a larger-than-ever vaccine market exists judging by the increasing incidence of valley fever cases in California, according to the most current survey. The California Department of Public Health publication “Coccidioidomycosis Cases—15 Counties, 2007-2011” even states that the numbers might actually be higher than reported since experts believe under diagnosis and under reporting are widespread.

For example, Imperial County reported only 37 cases for the five-year period 2006-2010 but considers itself an endemic area. Why then was the cocci rate so low? To answer that, in 2011 the county surveyed 102 providers and learned that only 43 percent considered cocci as a potential diagnosis in respiratory cases.

Note: these figures are before the recent construction of major wind and solar projects in western Imperial County, which released large quantities of dust in areas known to carry valley fever. (photo, right: Construction at Pattern Energy's Ocotillo Wind Energy Facility) Yet Imperial County’s website appears to have no mention of the disease, raising the question of whether physicians may be seriously under-reporting the actual number of cases.

Note: these figures are before the recent construction of major wind and solar projects in western Imperial County, which released large quantities of dust in areas known to carry valley fever. (photo, right: Construction at Pattern Energy's Ocotillo Wind Energy Facility) Yet Imperial County’s website appears to have no mention of the disease, raising the question of whether physicians may be seriously under-reporting the actual number of cases.

Ocotillo resident Edie Harmon, a biologist, raises this question regarding emergency room procedures. "Why don't the ERs in Imperial County have tests ordered for valley fever for the more than 33 % of cases of Community Acquired Pneumonia for which no pathogen was identified? Surely, the cost of the test is far less than the cost of treating the illness if not diagnosed or properly treated earlier when patients first seek treatment."

In general, cases in Imperial and San Diego counties increased sharply after 2009. Although Kern County (Bakersfield) had the highest number of reported cases (approx. 7,800) of all 15 participating counties, San Diego County with 650 cases ranked sixth highest in California. Interestingly, the southwestern corner of San Diego, adjacent to Mexico, appears to have the greatest incidence. Chula Vista accounted for 89 cases; the mean incidence rate is 7.5/100,000 compared with the City of San Diego’s rate of 4.5//100,000. Only 3% of San Diego County’s cases were in prisons, raising the issue of why a southwest urban area has higher rates than East County, where the spores are considered to be endemic. One possible explanation is that urban residents may be more apt to seek medical treatment than those in rural areas.

The number of cases has been rising countywide even before the latest troubling figures. San Diego County had a 43% increase countywide in valley fever cases from 1999 to 2000 and the disease has been on the rise here since 1990, epidemiologist Anne Kao found.

The good news, however, is that Nielsen Biosciences in San Diego has received the FDA’s approval for its Spherusol Skin test, and this diagnostic test will be available later this year. California’s prison system may take advantage of this. Another positive sign is the Flagstaff, Ariz.-based company Pathogene (now renamed DxNA) will launch an FDA clinical study in the next few months on a DNA diagnostic test for cocci. Todd Snowden says the company expects FDA clearance later this year. The test, which requires only an hour to run and is geared for small clinics, physician offices and veterinary hospitals, is based on technology licensed from TGen. Best of all, it’s simple enough for a nonprofessional to run on a small machine that sells for around $16,000. The hope is that this test, which probably will cost out at around $89, can diagnose the disease early on and thus improve health outcomes and lower costs.

Speaking of costs, Jie Ting, PhD and Leslie Wilson, PhD, both in the pharmacy department at University of California, San Francisco, presented a statistical analysis of the medical expenses incurred in California Valley fever patients.

For even the most common and treatable condition (uncomplicated pneumonia), direct lifetime cost per person is $18,800. Disseminated lifetime costs can run as high as $87,000 per person. Ting and Wilson concluded that Valley fever heavily impacts the state’s financial resources to the tune of $221 million annually.

Comments

Valley Fever

The University of Arizona has a new canine vaccine to prevent Valley Fever in development. Read all about it at

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/valley-fever-dog-vaccine/x/8676954#