By Miriam Raftery

By Miriam Raftery

April 21, 2012 (La Mesa) – La Mesa resident Frank Read, former proprietor of Read Pharmacy, celebrated his 100th birthday in November 2011—shortly before the city of La Mesa ushered in its centennial year in 2012.

In an exclusive interview with East County Magazine, he shared boyhood memories of our region—and recollections of his many adventures along the roads he’s traveled in his extended life.

Born November 24, 1911, Read grew up in San Diego at a home on L Street, but has fond memories of visiting La Mesa as a child to visit family friends, Arthur and Effie Johnson on University Avenue.

East of Park Blvd., San Diego, he recalls, “There was just sagebrush and canyons.” La Mesa’s houses were all clustered downtown near what was then called Lookout Avenue (now La Mesa Blvd.)

The Johnsons would come out with a horse and buggy to give young Frank Read a ride. “They had a cow and a horse,” he recalled. “They’d milk the cow and the three girls got on the horse and delivered their milk.” The family also kept chickens and had an orchard.

He recalled going to a store, where peanut butter was displayed in a big jar. “He’d put a big dab of peanut butter in a carton and fold it over,” he recalled. “Peas and beans? They’d dish it out and wrap it up. We didn’t’ have ready-made bags; we had to make our own wraps.”

Asked what kids would do for entertainment long before electronic games, TV or the Internet, he replied, “Ever see a kid roll a hoop with a stick? We’d take the spokes off a wheel wagon and we used to roll those all over.”

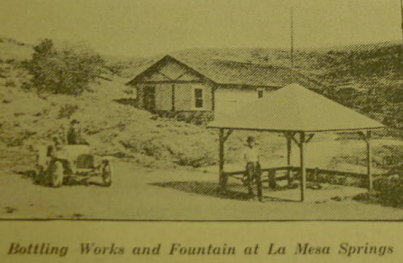

By his teenage years, he and the other kids enjoyed swimming n a swimming pool at Collier Park, where there was also a stone house for a caretaker. “At the corner of Pasadena and Collier Park there used to be a fountain,” he said. “People would come from the back country to fill their jars.”

By his teenage years, he and the other kids enjoyed swimming n a swimming pool at Collier Park, where there was also a stone house for a caretaker. “At the corner of Pasadena and Collier Park there used to be a fountain,” he said. “People would come from the back country to fill their jars.”

He recalled the wonder of watching helium-filled diriglbles flying through the sky in his youth.

On other occasions, he’d share different adventures with his friends. “We’d ride the number 11 street car out to Talmadge, now Fairmont. Past the other side there was a cave, built by a fellow named Young. It ran through the hill. We’d go through that cave sometimes and beyond that to Adobe Falls and swim. Now it’s all built up with houses,” he mused.

Read attended the brand new Sherman School in Sherman Heights, where his sister was a teacher. Later he went to Memorial Junior High and San Diego High School.

To get to high school, he recalled, “I rode the skunk car. It had a motor in front of the car, just a car on a a train track.”

Kids in those days roamed freely around town. “I used to ride a ferry,” he recalled. He also worked delivering newspapers starting at age 15. “I’d pack a lunch and a swimsuit. Transportation for kids then was a bicycle,” he recalled, adding that he would ride his bicycle down to the bay to swim. “I remember huge log rafts. They floated them from up north into the bay; they’d cut up these logs down here and tugboats would bring them down from up north.”

His parents were both from Michigan, where his father was raised on a farm, but didn’t like the farm lifestyle. “I went back to the farm when I was five and again around 12,” he recalled. “My Dad was in the Johnstown flood…He worked as a cook instead of in the mills…he moved around.”

After moving to San Diego,where Read was born, his father worked first as a fireman, then later for San Diego Gas & Electric. “They stored gas in big tanks, 50 feet across, 31 of them I think,” he recalled. “Dad worked at Station A for SDG&E, where they generated electricity.” In addition, he recalled, “They burned lamp black—made that into bricks that they sold for wood stoves. Of course there was no central heating in those days, and they burned very hot.”

As a young child, he recalls news of World War I. “I remember my mother reading the paper about all the casualties and being all upset.”

In his teens, he worked in a drugstore at 30th and Beech, where he worked as a soda jerk while going to school.

One of his friends in high school was Peter Crabtree, whose father was the track doctor at Caliente race track in Tijuana.

One of his friends in high school was Peter Crabtree, whose father was the track doctor at Caliente race track in Tijuana.

“I’d go down with the Crabtree family to the races. It was great,” Read said, smiling at the memories. “Pete and I would go down there. They’d have roulette going on in the clubhouse. WE didn’t have much money but we’d bet….Movie stars would come down there to the clubhouse.”

The stock market crashed in 1929, when Read was 17, sending the nation into an economic tailspin. “The Depession was a stinker,” Read said. “I’d just got out of high school. My folks wanted me to go to school but I was sick and tired; I wanted to get a job. Then the Depression hit and believe me, there was nothing.”

After graduating from high school with mostly A and B grades, Read attended Sand Diego State College which was then located on El Cajon Blvd while a new campus was being built in the current location of what’s now known as San Diego State University. “Everybody was saying `My God, why do they want to put it way out there in the sagebrush?” he recalled.

In college, he first took an engineering course, but after getting a D in calculus, decided he wasn’t cut out to be an engineer. “I realized a pharmacist will always have a job,” said Read, who went on to get a pharmacy degree at the University of Southern California.

At USC during the Prohibition era, some students would go out on Wilshire Blvd. “to a bootleg place and buy alcohol,” Read disclosed. Students would also buy “near beer” or soda, then “put alcohol in the neck and put a thumb on it and shake it.” Popular illicit drinks included highballs with orange soda, which students would imbibe at Colliseum Park. “Some people would make their own beer,” he added. “Prohibition was never successful.”

During his last year of school, he came home for a visit and a friend set him up on a blind date. “I wasn’t sure I wanted to do that,” Read confessed. But he soon fell in love with his blind date, Francis Mills, daughter of an orange grove owner in North Park. In October of 1933, he came home for another visit and proposed.

“There was a three-day wait to get married back then in California, but not in Arizona,” he recalled. “Her family had a six-cylindar Jewitt sedan and I had a little Durant Coupe I’d bought secondhand when I was going to state. We took my mother and her mother on a twisty, turny ride all the way to Yuma and we got married in 1933.”

Later, he recalled, “Fran and I lived with my folks in the room I grew up in as a kid. I came down, couldn’t get a job. I’d do anything—sweep floors.”

After getting his pharmacy degree but finding no jobs as a pharmacist, he went back to working as a soda jerk at his former employer’s pharmacy in San Diego. “I earned 25 cents an hour…My monthly take home was about $52.”

That was enough, however, for he and his new bride to rent a furnished single bedroom retanl unit on Fern Place. “It was very small, had a kitchen and bath, for $18 a month,” he said.

The newlyweds would sometimes go to the Hotel Del Coronado on Saturday nights, where dances were held. “They had a buffet…$1.75 or $2. Not very expensive for a couple,” he recalled. “They had an orchestra…We were dancing one night when lo and behold, I looked up and saw Gary Cooper,” he said of the movie star. “He was dancing.”

He worked for Marshall Eldridge, who lived in La Mesa and owned three drugstores in San Diego. Eventually, he got a job as a manager at a drugstore at 5th and University. Their first child, a daughter, was born in 1934.

Working at the pharmacy took its toll. “I worked nights one day, mornings the next, 15 hours. I worked one whole year with no days off, not even Sundays.” Finally, he recalled, “I asked for a day off.” The owner said “No way,” Read recalled. “That made me sore, so I said, `I’m going to quit. I was goingt o tell Eldridge I’d look for a job elsewhere…but he wasn’t there.”

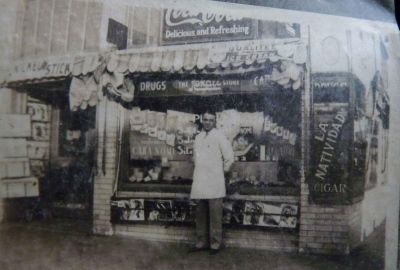

By chance, a salesman heard Read “spouting off” and told him about a pharmacist in El Centro looking for help. Then he heard about an opening in La Mesa, where he found work in 1935 at La Mesa Drug, working for Murray Kellogg, earning $100 a month at first. Photos taken in 1936 or 1937 show Read with two young women, including Jane Kellogg, the proprietor’s daughter. The pharmacy included a lunch counter, where workers from other businesses in town would come in to eat.

By chance, a salesman heard Read “spouting off” and told him about a pharmacist in El Centro looking for help. Then he heard about an opening in La Mesa, where he found work in 1935 at La Mesa Drug, working for Murray Kellogg, earning $100 a month at first. Photos taken in 1936 or 1937 show Read with two young women, including Jane Kellogg, the proprietor’s daughter. The pharmacy included a lunch counter, where workers from other businesses in town would come in to eat.

In La Mesa, Read and his young family lived in a court with small houses close together “where the old police department was. By then, things had expanded east, south and west,” he recalled.

Tragedy soon struck the young couple. Fran gave birth to twin boys. A week later, one of the infants died. “The other died three weeks later or so,” Read said, a shadow creasing his face. “The pediatrician said that very often, with twins, if something is wrong with one, there’s a problem with both.” An autopsy showed one boy had an intestine that wasn’t connected and the other had a weak heart.

In 1940, the couple had another son, who thrived and today lives in Santee.

Read has many memories of La Mesa in that era. On the southwest corner of Palm and Lookout was a grocery store where a friend, Carl McCarthy, worked at a meat counter.

“The fire department had a shed with a volunteer fire department just this side of the tracks,” Read recalled, “north of La Mesa Blvd. There was a big iron ring. If there was a fire, they hammered it with a sledge hammer—that was the fire alarm. I’d see Carl and this other fellow run out in their aprons,” he said, noting that his friend doubled as a volunteer firefighter.

noting that his friend doubled as a volunteer firefighter.

The same block had a drug store further to the west, as well as an Italian market. “On the north side right in the middle was a hotel. Mrs. Marshall was a widow, she ran the hotel. Vera Marshall was a pretty girl; she won a beauty contest and she worked in the pharmacy.” He also recalled bank manager Harry Griffin, for whom a park was later named.

Read recalled the challenges of taking a vacation in those early years of his marriage. “We didn’t have any money. We were living in that court and we gave that up. I got a gas credit card and we took our money we’d have paid for rent. “

In those days, travelers carried their own blankets, he explained, to stay in a “Shanty” with a mattress bed that you’d make up yourself, along with a washbowl and a couple of chairs. “So we took off, going up the coast. Maybe you’d pay 50 cents deposit in those days” for lodging. Arriving in Portland, Oregon, they found that a convention in town had filled up all the lodging. Eventually they paid $1.75 for a room and rode a birdcage elevator to an upper floor—where a three-foot-wide walkway with a bed covered by a white spread awaited the weary travelers.

“My wife flopped out on it. She had her hands out and said `It feels funny.’ It was an old straw mattress!” Read said. “We went back downstairs and got our money back. They wound up in a hotel that charged them $2 a night. “Across the street was a theater marquis, flashing on and off all night.”

Back in La Mesa, men in the 20s and 30s joined a 20/30 club. “We’d have dances down there in the clubhouse above La Mesa Golf Course,” he said, adding that the location was near Highway 94. Popular dances then included waltzes and foxtrots.

During World War II, Read recalled friends who were called to serve in the war, including Walter Barnett, principal of the high school. Read was classified a “3”, he recalled, adding that he felt like a “slacker” for not marching off to war. But since he had two children and worked in La Mesa Drugstore, he recalled, “They said you’re more needed here.”

In those days, filling prescriptions meant that everything had to be compounded—or mixed from scratch. Ingredients were crushed with a mortar and capsules filled with the powders. Before vitamins were made commercially, pharmacists sold emulsions of foul-tasting cod liver oil.

Read worked at La Mesa Pharmacy until after the war ended. “Then I quit and went with a detail man. We’d go out and call on doctors to sell them drugs—penicillin, stuff like that, was brand new back then,” he recalled, adding that penicillin cost $1 a tablet. “That was a lot of money.”

He didn’t like selling drugs to doctors. Safter a short time he gave that up and did relief work. That meant filling in for other pharmacists who wanted a day off at stores in La Mesa and National City.

Eventually he decided to buy a lot at La Mesa Blvd. and Randlett, across from Little Haven Flowers, where he built a building and established Read Prescription Pharmacy. “The building had doctors and dentists; I was there for many years,” he recalled.

After his youngest child graduated from high school, he sold the business and went to work for Grossmont Hospital, which had been built in 1955. “The hospital expanded two or three times when I was working there,” he said. Starting in 1963, he worked at the hospital until November 1977.

One of his more colorful memories involves driving trips with a friend in his ’36 Plymouth sedan that he’d purchased for $900. “Those were the days,” he recalled. “We’d go fishing up in the Sierras.”

One time, he took two Benzedrine tablets, the first amphetamines, on the way back to stay awake on the long drive home on a two-lane road. “I didn’t notice anything, so I took another. I was hopping—I couldn’t sleep all that day and the next night,” he recalled. “I never took another.”

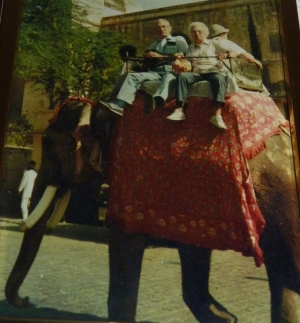

After his retirement, he and his wife enjoyed traveling around the world. “We took a lot of trips. We went to China in 1982.” Gesturing toward a wall in his home, he observed, “Those items are from New Guinea. I went on safari in Kenya, and I was in Morocco once.” He even rode an elephant.

After his retirement, he and his wife enjoyed traveling around the world. “We took a lot of trips. We went to China in 1982.” Gesturing toward a wall in his home, he observed, “Those items are from New Guinea. I went on safari in Kenya, and I was in Morocco once.” He even rode an elephant.

On New Year’s Eve in 2002, his beloved wife of 69 years passed away. Since then, he’s continued to make the most of life, spending time with his daughter, who lives in Capitola near Santa Cruz, his oldest son in Santee, and youngest son in Tucson. He’s traveled with his son to the Sierras and to Reno, Nevada. “I like British Columbia, Victoria,” he said of a trip to Canada. “And we went down the Amazon.”

Still spry at 100, Frank Read continues to drive and live independently in his La Mesa home on Windsor hill.

Asked what he expects La Mesa to be like in the next 100 years, however, he concludes, “They’re going to have to revitalize some places,” noting that neighborhoods where he once lived have become run down in recent years. But after a century of living, he’s come to embrace changing times. “They’re probably going to have to tear some of those places down,” he concludes, “and build new ones.”

Comments

Frank Reed passed away today, Dec. 26, 2019.

He was 108 years old -- may he rest in peace.