District disputes statements by residents criticizing its actions

By Miriam Raftery

By Miriam Raftery

February 10, 2023 (Alpine) – Despite heavy rains in January that have alleviated severe drought concerns, Sweetwater Water Authority on January 26 announced that it has initiated a new transfer of water from Loveland Reservoir to Sweetwater Reservoir. The new transfer comes after a controversial transfer begun in November drained Loveland down to dead pool status for the first time in the district’s history, raising concerns over negative impacts on wildlife, firefighting resources, and loss of recreational use including fishing.

Last month, heavy rains caused major damage to a floating fishing dock, as well as substantial erosion, as ECM reported. Now, the district has announced that “due to safety concerns, the Recreation Program at Loveland Reservoir is closed until further notice. Recent rains caused significant erosion in the Recreation Program area at Loveland Reservoir. For the safety of the community, the program will remain closed until further notice. Sweetwater Authority staff will be assessing the damage and evaluating options for repairs in the coming months.” For the latest updates, visit www.sweetwater.org/recreation.

Darlene Cosso, board member and spokesperson for the newly formed Friends of Loveland Reservoir, told ECM, “Friends of Loveland Reservoir would like to collaborate with Sweetwater Authority to propose solutions to the repeated draining of the lake. We believe we have various options which will benefit community members, the environment, wildlife that depends on Loveland, and Sweetwater Authority and its customers.”

Friends of Loveland Reservoir posted the following call to action on its Facebook page, for residents upset over the closure and repeated draining:

Have you heard all access to hiking and bird watching at Loveland Reservoir has been closed. How many of you enjoy these activities in this area? Please reach out to your representative to share your feedback about this action. Please remember to remain positive and provide solutions. We want to work together. Thank you!

Contact information:

Robert Heiar robert.heiar@usda.gov

Scott Tangenber scott.tangenberg@usda.gov

Supervisor Joel Anderson joel.anderson@sdcounty.ca.gov

Supervisor Nora Vargas nora.vargas@sdcounty.ca.gov

Supervisor Nathan Fletcher nathan.fletcher@sdcounty.ca.gov

Supervisor Jim Desmond jim.desmond@sdcounty.ca.gov

Andrew Hayes andrew.hayes@sen.ca.gov

David Alvarez david@davidalvarez.com

Joaquin Esquivel joaquin.esquivel@waterboards.ca.gov

Brian Jones brian.jones@sen.ca.gov

January rains had refilled about half the water drained from minimum pool to dead pool status, raising hopes among recreational enthusiasts and environmentalists that the lake might ultimately recover from the severe draining. But the second draining has dashed those hopes, and critics contend that the district's newest draining was unnecessary as well as destructive

January rains had refilled about half the water drained from minimum pool to dead pool status, raising hopes among recreational enthusiasts and environmentalists that the lake might ultimately recover from the severe draining. But the second draining has dashed those hopes, and critics contend that the district's newest draining was unnecessary as well as destructive

. California’s drought is not over. But the San Diego region has seen its drought level lowered to D1 “moderate drought” level, the second lowest level in the state’s five-level ranking of drought conditions.

So if a second draining isn’t immediately needed to meet the district’s water supply needs, why did the Sweetwater Authority choose a second extreme draining, without regard to killing off fish, birds or other wildlife reliant on the lake, the fire concerns of residents with firefighters forced to go to lakes further away for water to fight fires, and the recreational desires of fisherman, birdwatchers and hikers?

In a statement to ratepayers, General Manager Carlos Quintero confirms, “Late December and January brought substantial rainfall to the region. However, after four years of dry weather patterns, we are still in need of water. Sweetwater Reservoir is below 40 percent capacity. These transfers are standard operational practices that we conduct to secure the water supply for our customers.”

But there’s more than water supplies at stake. Critics contend the district’s decision to decimate Loveland Reservoir when the district overall has enough water to meet 40% of its water needs from its reservoirs is all about the money. The district estimates that the two transfers will save $11 million for Sweetwater ratepayers, by avoiding the cost of purchasing water from other sources, as some other districts have done.

Russell Walsh, an avid fisherman and activist who has become the district’s most vocal critic over its actions at Loveland, blames the closure of the lake squarely on Loveland’s draining of the reservoir to such low levels.

“The lake is closed for safety reasons. That’s the erosion Sweetwtater caused,” adding that the raining also resulted in destruction of the fishing float funded by HUD. Now, he says,”The new bluffs are bad and in the most trafficked area. They screw up, we pay, and in Sweetwater’s words, “indefinitely. Who thinks they are motivated to fix this?” He adds, “In 75 years, the lake never became dangerous.”

Sweetwater has raised objections to some statements made by Walsh and another speaker during public hearings and statements published by East County Magazine in our article on damage to the fishing float.

In a letter signed by Carlos Quintero, General Manager, the district noted that the fishing float was already left on dry land before the first controlled water transfer. Walsh responds that the reason the dock was left on dry ground and destroyed in the first major rains of 2022 is “because in January 2021, Sweetwater drained the lake, including at least 1,000 feet of the historical minimum pool. Sweetwater is wrong to call these latest water policies `controlled transfers’” he contends, adding, “Nothing controlled causes this much environmental and property damage and human heartbreak.”

Sweetwater also objected to Walsh’s statement that the dock destruction (photo, left) would not have happened if Sweetwater left minimum pool in there like they promised and Congress in their grant solicitation.”

Sweetwater also objected to Walsh’s statement that the dock destruction (photo, left) would not have happened if Sweetwater left minimum pool in there like they promised and Congress in their grant solicitation.”

Walsh says the reservoir’s banks were left as “sitting ducks” for massive erosion after the January 2021 draining. “Sweetwater would like to spin the massive erosion and destruction of the public fishing dock as an act of God. The board of directors ignored historical practices of maintaining the flood water attenuating minimum pool, and that gamble failed. Much of the erosion went west towards the dam and water work.” He suggests that the economic consequence of needed repairs now could offset water acquisition cost savings, adding that such damage could become worse without restoration of the minimum pool.

According to Sweetwater’s email to ECM, “There has never been a promise of a minimum pool for the Loveland Recreation Program. Documents for the grant indicated the installation of a fishing float, which could be moved as required to accommodate fluctuating reservoir water levels and to provide a stable fishing platform for anglers, however this can only be moved within the limits of the recreation area.”

Walsh has long claimed that Sweetwater Authority was required to protect fishing as part of a 1996 Forest Service/Sweetwater land swap deal. ECM reported in depth on these claims here in an article by award-winning investigative journalist Elijah McKee who found the Forest Service in recent years has ducked responsibility to enforce the deal that many believed was intended to protect recreational access at the lake.

Walsh insists that Sweetwater was required to protect fishing as part of the 1996 land swap, and that Sweetwater “chose to comply by relocating fishing to the east end of the lake. The public and even a California Agency, the Department of Fish and Game, now Fish and Wildlfie, protested the potential loss of fishing in low water periods to…the Descanso Ranger.” To induce cooperation on the land swap, Sweetwater Authority staff provided the ranger with a “synopsis that included a promise of levels of water suitable for the stability of wildlife habitat and recreation, even in periods of drought exceeding those seen in the 19 years previous to the land swap.”

According to Walsh, “Long-time Sweetwater engineer Ron Mosher admitted it was likely Sweetwater provided the promise of water in the fishing program, but said, “unfortunately, we do not have the documents that were likely to have provided that information,” in response to Walsh’s public records requests. “There is much more convincing evidence in Forest Service and Sweetwater land swap origination documents, some of which have been covered in previous ECM articles.”

Sweetwater also countered Walsh’s statement that a bond measure passed by district ratepayers was “specifically pushed by the division of safety of dams to correct problems at Sweetwater Dam” and his contention that some items specified in the bond, such as fixing Loveland’s stairwell and Sweetwater Dam, were not done. Walsh said the agency didn’t merit public funds due to its treatment of bond money, particularly “bond money gotten by order of the division of Safety of Dams.”

An assessment by the state on dam safety, last done before the January rains, found Loveland in satisfactory condition but with a high hazard level should it be breached (meaning high potential loss of life or property). The state found Sweetwater in Fair condition, also with a high hazard level. The Sweetwater Dam previously suffered damage in a 1916 flood.

An assessment by the state on dam safety, last done before the January rains, found Loveland in satisfactory condition but with a high hazard level should it be breached (meaning high potential loss of life or property). The state found Sweetwater in Fair condition, also with a high hazard level. The Sweetwater Dam previously suffered damage in a 1916 flood.

Photo, right: Loveland Dam after January rains

Sweetwater fires back on Walsh’s criticism, “There were several eligible projects to use the mentioned bond money funding, with the Sweetwater Dam improvements/repairs being one of them. However, the Division of Safety of Dams ordered a Comprehensive Assessment of Sweetwater Dam after final design plans for Sweetwater Dam improvements/repairs were submitted to the Division of Safety of Dams (DSOD) for approval, putting a halt to previously proposed improvements/repairs at Sweetwater Dam until the Comprehensive Assessment is completed, estimated in October 2024.” Therefore, bond funds were used on other projects, the district’s statement adds.

Walsh calls Sweetwater’s response “irresponsible,” noting, “Delayed Sweetwater dam repairs go back at least to 2003,” 20 years ago. He recalls that this particular bond was pushed by then-director of the Division of Safety of Dams, David Guitierrez, “during an angry 2016 in-person visit to a Sweetwater Board meeting.”

Walsh calls Sweetwater’s response “irresponsible,” noting, “Delayed Sweetwater dam repairs go back at least to 2003,” 20 years ago. He recalls that this particular bond was pushed by then-director of the Division of Safety of Dams, David Guitierrez, “during an angry 2016 in-person visit to a Sweetwater Board meeting.”

Walsh did acknowledge that some projects on which bond money was spent were listed in the bond, but questioned whether the scope of work cited justified the among of funds spent, noting that Sweetwater’s lobbyist last year “asked for taxpayer funding to accomplish long-delayed progress on the dam safety and retrofit issues at Sweetwater and Loveland Reservoirs.” At recent audiotaped meetings, Sweetwater’s directors have “shown disdain for new pressure from DSOD to fix the dam, claiming the reservoir will never be that full and that they would instead focus on sand mining at the Sweetwater Reservoir in Spring Valley. The whole conversation about funding the work on the dams should be audited,” Walsh suggested.

Sweetwater Water Authority took issue with Walsh’s remarks suggesting that drought was not a sufficient reason to drain the lake so low, given water levels at state reservoirs, and Walsh’s claim that a need to drain the lake or change valves was a “hoax.”

According to Sweetwater, “Local water is far less expensive to produce than imported water from Northern California or the Colorado River. Although there are plans to replace valves at Loveland Dam in the future, the controlled water transfer initiated on November 15 was to address local drought conditions and not to replace the valves at Loveland Dam.”

Walsh contends Sweetwater is failing to comply with its mission statement, which requires the district to provide customers with a safe and reliable water supply that includes “a balanced approach to human and environmental needs.” Walsh opines, “After witnessing the dislocation of wildlife, especially birds, and the destruction of their minimum pool-based habitat and food chains, and the broken hearts over the recreation and aesthetic damage, and also the damage to fire protection resources in a fire-prone area, it’s safe to say anything Sweetwater says about balance, the environment or human needs, at least as far as it extends to Loveland Reservoir, is lip service at best.”

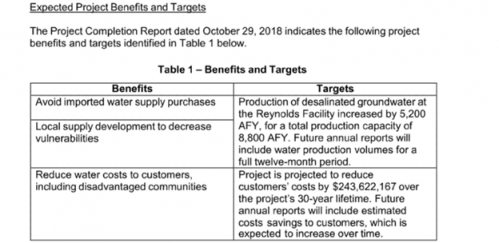

He notes that Sweetwater’s demand for water is actually down from 24,000 acre-feet per year when the land swap was made, down to 16,000 acre feet currently. He suggests Sweetwater has manipulated drought issues, avoiding admitting the large decrease in demand for the district, and downplayed new inexpensive local water supplies from a 2018 desalination plant expansion that Federal and State taxpayers contributed to in grants worth $31.5 million, or 75% of the cost. This allowed the district to produce “more than half the remaining 16,000 acre feet” leaving only 8,000 to 10,000 acre-feet to come from sources Sweetwater had at the time or the land swap, yet records indicating Sweetwater started draining local water in 2018 after the desalination plant was finished. A 2018 annual report to a desalination plant grantor concluded that Sweetwater customers could expect at least $243 million in benefits over 30 years

AS for fire safety, Quintero also sought to counter concerns raised by resident Mike Simpson in public testimony. Simpson stated that due to draining Loveland to dead pool level, “if property burns or citizens are injured because of lack of water to put out fires, Sweetwater would be liable and responsible.”

Quintero says that before the Nov. 15 controlled water transfer, “Cal Fire did not raise any concerns and indicated that if any lake water would be needed for firefighting purposes, that they would just go to a different water source and would note on their map of available water sources that Loveland might not have sufficient water.”

That response sparked ire in Walsh, who says the district “mischaracterized facts and is unempathetic. Regardless of whether Cal Fire was consulted or cared to be consulted, the experience of the people living around the lake, far removed from where any Sweetwater board members live or are elected, know the fire protective value of the approximately 5-mile-long body of water at the minimum pool standing between Alpine, Dehesa, and Jamul and of the firefighting benefit minimum pool provides. Citing Cal Fire is a cop out. Residents have witnessed extensive use of a large variety of aircraft” dousing fires with water scooped out of Loveland, he says, adding that Simpson’s concerns are “broadly shared in the fire-prone region.”

Quintero concluded his letter on behalf of Sweetwater Authority by pointing out that Loveland Reservoir “has been operated as a water supply facility since its construction in the mid-1940s. Recreation activities, such as fishing, have been allowed provided there is sufficient water storage. At no point in time has Sweetwater Authority, or its predecessors, relinquished water rights for fishing or any other purpose.”

Walsh concluded, “Given that this board doesn’t care about its legal obligations at Loveland, it also seems hellbent on providing a complete lack of empathy. AT no point in the history of the lake did any previous board of directors did “so much damage to the wildlife and the people who depend on Loveland’s minimum pool.”

He scoffed at the district’s promise to allow fishing in times of “high water” noting, “The water district has killed most, if not all, fish and has a policy of draining water whenever there is any to take. How can there ever be fishing? Worse, constant filling and unfilling of the pool will create a vicious cycle-type disturbance for wildliffe” that depends on the water source. Even if wildlife population begins to recover after a future rainfall, Walsh observes, “Sweetwater will destroy it as soon as it does. I guess they better rewrite their mission statement.”

The problem points up an inherent inequity in the local water supply system. The people who care most about saving Loveland Reservoir in Alpine -- it's neighbors and outdoor enthusiasts in the area -- cannot vote for the directors of the Sweewater Water Authority, who are elected by South Bay voters and not beholden to the people who love Loveland.

Recent comments