Rural areas and historic districts are exempt from landmark laws that change single-family zoning to allow more housing in some communities

Rural areas and historic districts are exempt from landmark laws that change single-family zoning to allow more housing in some communitiesBy Brian Schrader

October 2, 2021 (San Diego) — In September, Governor Gavin Newsom signed two new housing bills into law. The main bill, titled SB-9, and its companion bill SB-10 are the work of California Senator and San Diego native Toni Atkins. Together, they represent the most sizable shift in California land use policy in recent decades.

SB-9 focuses exclusively on reforming single-family zoning, a type of zoning that accounts for 7.5 million parcels in California. The bill gives two new options to the owners of single-family lots. The first provision allows homeowners to build an additional home on their property, which would result in two homes per lot. The second allows homeowners to split their lot in two. Together these provisions allow homeowners to construct up to three additional units on their property. New units could be attached duplexes or detached granny flats. The law also standardizes the rules for constructing additional units and introduces some measures to ensure that lots are concentrated in urban areas and that homeowners control the process, not housing developers.

Before a lot can be split under SB-9, the bill requires that the homeowner commit to live on the property for at least three years. The law does not apply to historic districts and does not allow homeowners to demolish units providing certain kinds of low-income rental housing.

In a recent press release, Atkins’ office stated that SB-9, "widens access to housing for California’s working families and provides homeowners with more options to create intergenerational wealth."

The bill has so far received both strong praise from its supporters and strong condemnation from its opponents. Supporters say that SB-9 generates additional housing for California’s undersupplied housing market by effectively allowing millions of Californians the option to build more housing in single-family neighborhoods without requiring localities to re-zone the land—a task that can take years to complete. The bill’s opponents argue that the law circumvents local control of zoning and could lead to overburdened residential infrastructure, a change in neighborhood culture, and a lack of parking.

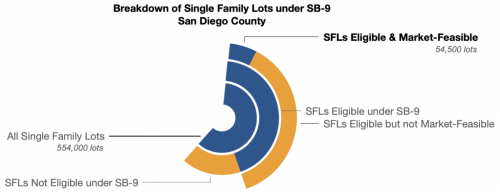

According to the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at U.C. Berkley, the real effects of SB-9 are most likely somewhere in the middle. In an analysis published in July, the Terner Center estimates that while California does indeed contain 7.5 million single-family lots, only about 6.1 million are eligible for improvements under SB-9. The report further estimates that only around 410,000 parcels are market-feasible, meaning that the new units and lot splits enabled by the bill are likely to recoup their costs when rented or sold at the going market rate. In San Diego County, the report estimates that out of over 554,000 single-family lots, only about 54,500 are both eligible for improvement under SB-9 and likely to be market feasible—about 9.8%.

According to the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at U.C. Berkley, the real effects of SB-9 are most likely somewhere in the middle. In an analysis published in July, the Terner Center estimates that while California does indeed contain 7.5 million single-family lots, only about 6.1 million are eligible for improvements under SB-9. The report further estimates that only around 410,000 parcels are market-feasible, meaning that the new units and lot splits enabled by the bill are likely to recoup their costs when rented or sold at the going market rate. In San Diego County, the report estimates that out of over 554,000 single-family lots, only about 54,500 are both eligible for improvement under SB-9 and likely to be market feasible—about 9.8%.Steven Dietz, a Los Angeles based Accessory Dwelling Unit Developer, spoke about the potential and the limitations of the new law on the Capitol Weekly Podcast. During the conversation, Dietz spoke about the mechanics of the bill. He explained that under prior law "the only way for someone to build a home for somebody else is to increase the mortgage on their own home. Basically, they would need to borrow against their home in order to build one for another." Under the new law, lots can be split which enables new construction to be "financed independent of the main house." He stipulates that those provisions could result in the law being much more impactful than previous attempts to improve California’s housing supply.

Further provisions in the law limit potential construction to lots within an "urbanized area or urban cluster, as designated by the United States Census Bureau." San Diego County’s urbanized areas exclude any land east of Alpine as well as areas with at least 50,000 residents or less than 1,000 per square mile. These criteria ensure that new development is concentrated in urban areas, where new housing is most necessary.

The other bill, SB-10, is aimed at solving California’s housing dilemma. It allows cities to streamline the process of approving developments with up to 10 units near transit locations that used to be single-family homes. The bill exempts qualifying projects from review under the California Environmental Quality Act—a law that is often abused by opponents of new housing in order to delay development projects for years.

The other bill, SB-10, is aimed at solving California’s housing dilemma. It allows cities to streamline the process of approving developments with up to 10 units near transit locations that used to be single-family homes. The bill exempts qualifying projects from review under the California Environmental Quality Act—a law that is often abused by opponents of new housing in order to delay development projects for years.Together, the two bills mark the latest attempt by California legislators to address the state’s housing crisis. SANDAG estimates that the County needs an estimated 171,685 new housing units by 2029 in order to meet demand—with about 16,000 in East County. California’s housing crisis has led to rising rents, record-breaking home prices, and an increase in homelessness across the state. Experts see the problem only getting worse unless more housing is built to meet demand.

The vote for SB-9 among San Diego County representatives was largely split along party lines with the exception of North County Democrat Tasha Boerner-Horvath joining with Republicans in opposing the bill.

The vote for SB-10 was also split largely along party lines, this time with the exception of East County Republican Brian Jones, who joined with Democrats in approving the bill.

Assembly-member Brian Maienschein, another North County representative and Democrat, did not vote on either bill.

Recent comments