By Miriam Raftery

By Miriam Raftery

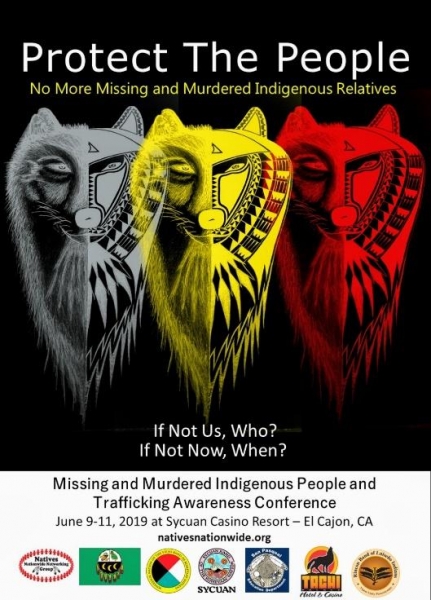

June 18, 2019 (Sycuan) – Members of sovereign tribes from across North America convened at the Sycuan resort in San Diego’s East County June 9-11 for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People and Trafficking Awareness Conference.

Murder is the third leading cause of death among Native American and Alaska Native women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Men and boys have also gone missing and been killed.

The rates of missing indigenous persons and those targeted by violence are shockingly high in the U.S. and Canada, yet official statistics are scarce and almost certainly undercount these cases, which are also too often not reported by media.

“Men are stepping up now, saying, `Not one more,’” Lupe Lopez (photo, right), a counselor and workshop leader, said. “We are not for sale. We are marching. Even in the women’s march, we are taking the lead.”

“Men are stepping up now, saying, `Not one more,’” Lupe Lopez (photo, right), a counselor and workshop leader, said. “We are not for sale. We are marching. Even in the women’s march, we are taking the lead.”

The National Crime Information Center reports that in 2016, there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls. Yet the U.S. Department of Justice’s federal missing persons database, NamUs, only logged 116 cases.

Violence on reservations can be up to 10 times higher than the national average and in the U.S., most of the violence is perpetrated by non-Natives, though domestic violence is also a problem.

That figure doesn’t count the 71% of Native Americans and Alaska Natives who live in urban areas, so the Urban Indian Health Institute requested data for 71 cities in 29 states. Not all jurisdictions provided records.

The UIHI was able to document 506 cases of missing and murdered American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls, with two-thirds of those cases from 2010 to 2018. Over half --56%-- were murder cases, and 28% of perpetrators were never held accountable.

Of those 506 missing or murdered, 8% involved domestic violence, but most did not. Some victims had been trafficked into the sex trade; 6% of the women and girls had been sexually assaulted at the time of their disappearance or death. Six were murdered by a serial killer. Eight were homeless and seven were victims of police brutality or died in custody.

Nationwide, many of the murders are by non-Native strangers. The movie “Wind River” is based on the true story of indigenous women raped and killed by oil workers on their reservation in Wyoming.

Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind (photo, left) was eight months pregnant when she disappeared in North Dakota in 2017; she was brutally murdered, her unborn baby cut from her womb. Savanna’s law, a bill that aimed to improve the reporting and investigation of missing Indian and Alaskan native women has thus far stalled in Congress.

Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind (photo, left) was eight months pregnant when she disappeared in North Dakota in 2017; she was brutally murdered, her unborn baby cut from her womb. Savanna’s law, a bill that aimed to improve the reporting and investigation of missing Indian and Alaskan native women has thus far stalled in Congress.

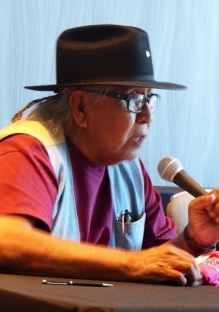

“Check to see how many tribal deaths have ever been solved. You won’t find it,” Preston Arrow-weed of the Quechan tribe said in a panel of tribal elders.”Every race is there [in crime statistics] ut not Native American, because they don’t care.” Arrow-weed (photo, right) faults not only the U.S. government and local police, but also tribal leaders who turn a blind eye to the problems.

“Check to see how many tribal deaths have ever been solved. You won’t find it,” Preston Arrow-weed of the Quechan tribe said in a panel of tribal elders.”Every race is there [in crime statistics] ut not Native American, because they don’t care.” Arrow-weed (photo, right) faults not only the U.S. government and local police, but also tribal leaders who turn a blind eye to the problems.

“My grandson went all the way to Washington D.C. because a tribe had put a casino on a sacred site,” he says. His son went to sing fight songs with the American Indian Movement. “He came home and they killed him for that…The tribe, the FBI did nothing. The County sheriff was covering up. I’m still trying to find someone who will do something. We should make all officials accountable.”

Deeply rooted in traditional tribal ways, Arrow-weed sees violence and suicide as stemming from abandonment of ancient tribal ways by some of the youths today. “Violence in tribes is because of assimilation,” he says.

Arrow-weed joined many younger runners in a run from his Fort Yuma, Arizona reservation to Sycuan to draw attention to the issue of missing and murdered indigenous people. Their arrival marked the start of the conference Sunday night. (Photo, left)

Arrow-weed joined many younger runners in a run from his Fort Yuma, Arizona reservation to Sycuan to draw attention to the issue of missing and murdered indigenous people. Their arrival marked the start of the conference Sunday night. (Photo, left)

Arrow-weed has taken other brave stances, such as running 200 miles with students to protest burial of nuclear waste along the Colorado river, a cause he views as noble. “Support the noble people,” he implores.

Others echoed the sentiment that abuse and trauma in Native American communities has its roots in colonialism. Before the arrival of Columbus, tribes in North America had mostly peaceful existences, with emphasis on caring for families and the land. Manifest Destiny brought white colonizers bent on conquering natives, removing tribes off native lands and destroying property. The Mission system enslaved Native Americans, whose children were later forced into Indian schools.

“Many suffered abuse, which was passed on in our own families,” Lopez says. Tearfully she revealed that her own daughter went missing, but fortunately came home. “I walk in these shoes. Maybe God put me through this for a reason – to help you,” she tells the audience.

Jacquie Nunez, another elder, says spirituality is missing among native children who have often not been taught about their own culture. She now teaches both Indians and non-Indians. She shared a heart-breaking story about a niece, 13, who was found in a hotel with men; when asked why she said she wanted to be like her mother, a prostitute who had lost custody of her five children. She later committed suicide. “I will never forgive myself,” Nunez says of missing the signals of depression.

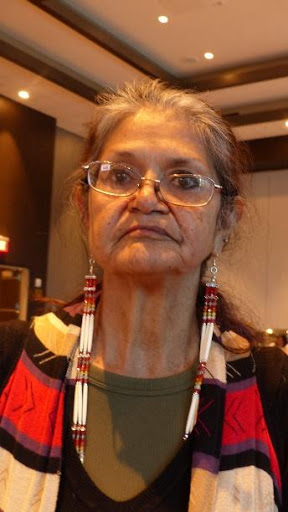

Grandma Sioux (photo, right), now an elder, recalls, “As a child, I was raised with respect. No hitting, no anger, no gossiping. I didn’t know what those actions were. Grandmas were heads of families; we never spoke back to adults.” But in the 1950s, alcohol came to her reservation and made her uncle “crazy.”

Grandma Sioux (photo, right), now an elder, recalls, “As a child, I was raised with respect. No hitting, no anger, no gossiping. I didn’t know what those actions were. Grandmas were heads of families; we never spoke back to adults.” But in the 1950s, alcohol came to her reservation and made her uncle “crazy.”

She was removed from her home at age 9 after her grandmother died and was then sent to Indian school and later foster homes, where she was hit by a foster parent in the mouth with a fist. “I learned how to be cold-hearted,” she recalled. “As a teen, to stop the pain in my heart, I tried alcohol and I liked it. I became addicted. I took it into my own family and I became a hurtful, hateful parent. “ Ultimately, she sought out help from Alcoholics Anonymous. “Don’t be ashamed to get help,” she tells others.

California has had 40 missing or murdered indigenous women and girls – the sixth highest level in the nation.

American Indian and Alaskan Native children who have been in the child welfare system have a 50-90% higher risk of victimization than any other racial or ethnic group, says Trish Martinez, who gave a presentation on human trafficking at the conference.

American Indian and Alaskan Native children who have been in the child welfare system have a 50-90% higher risk of victimization than any other racial or ethnic group, says Trish Martinez, who gave a presentation on human trafficking at the conference.

“They are targeted by traffickers,” she says, noting that traffickers target children who are runaways as well as youths with low-self esteem or substance abuse issues. Suicide rates are high on reservations, including among some children who have been trafficked or abused, “because we are missing the signs,” says Martinez.

Trafficking has also been documented on the U.S.-Canadian border as well as locally on the U.S.-Mexican border. In Canada, indigenous women are six times more likely to be murdered than other women. Estimates on the number of Canadian indigenous women who have gone missing or been murdered from 2000 to 2016 range from 1200 to 4,000, prompting the Canadian government to launch a national inquiry.

Locally in San Diego County, Martinez warns that gangs and traffickers are active “in schools our children attend.” She urges parents to watch for signs that a child is in trouble. “Look at their cell phones. Be concerned. If a child becomes silent, ask `What happened to you?’” Then be prepared to hear uncomfortable truths, she says, adding, “You’d better damn well believe them.”

She recalls here own teen years as a child of an alcoholic father. “I was running, drinking, my mother never found it.”

The Indian Child Welfare Act enacted 40 years ago is helping to protect native children, Martinez says. Before it was passed, in 1978, 25 to 35% of al American Indian and Alaskan Native Children were removed from their homes into the child welfare or adoption systems and 85% were placed outside their communities – even when their were fit and willing relatives.

Here in San Diego County, there were 500 American Indian and Alaskan Native children in the system. “Now we only have four in our county’s child welfare system. The rest have been brought home,” she says. But 56% of those who are removed wind up placed outside their families and communities “We need more Indian homes,” she says.

She holds up a trash bag for emphasis. “This is a suitcase,” she says, noting that foster children carry all of their belongings inside. “How do you think that makes them feel? Our kids are looking for identity…they’ve been traumatized.”

Several local parents of missing or murdered children spoke at the conference about their journeys and agreed to interviews with East County Magazine.

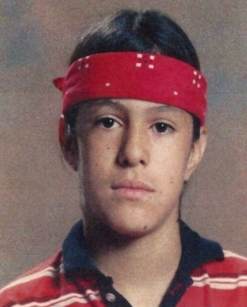

“Unless you’ve been there, you really can’t fathom it,” says June Christman (photo, right). Her son, Shawn “Lone Wolf” Christman went missing in 1993. It took 26 years to learn that his body had been washed up on the shore of Lake Michigan the same year he vanished—after a caring police officer finally agreed to enter his DNA into a national federal database called NamUs.

“Unless you’ve been there, you really can’t fathom it,” says June Christman (photo, right). Her son, Shawn “Lone Wolf” Christman went missing in 1993. It took 26 years to learn that his body had been washed up on the shore of Lake Michigan the same year he vanished—after a caring police officer finally agreed to enter his DNA into a national federal database called NamUs.

Now June Christman’s goal is to get a national law enacted to required that every missing person’s DNA be entered in the NamUs database. At the conference, she made a big step toward making that happen, meeting Mike Woods, a consultant with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children who agreed to support her efforts.

Heather Rollins came to the conference with 4-year-old son. (Photo, left)

Heather Rollins came to the conference with 4-year-old son. (Photo, left)

“His dad was murdered in Valley Center,” Heather told ECM. She and her son wear T-shirts with his image to keep his memory alive.

The relative who stabbed and beat her boyfriend, father of her son, while he was sleeping was sentenced to just three years for involuntary manslaughter. “I’m angry,” she says. “No justice was found because of a wealthy lawyer.”

LeLanie Joe Thompson’s son, Elijah Runningbear Diaz, has been missing since August 29, 2015.

“There is nothing the police can do, because there is no proof that he’s been killed,” she says. Elijah’s DNA is in the NamUs database, but no match has been found. Yet LeLanie has lost hope that he could be found alive.

“He was too sick. He was about to get his foot amputated. He couldn’t walk. He was in a wheelchair a few days before.” A diabetic, he had only two weeks of insulin, never used his health insurance and never picked up his paycheck after disappearing from the family’s home.

”Somebody came and picked him up and took him somewhere,” LeLanie (photo, right) theorizes. “I believe we’ll get an answer someday. Somebody knows.” The family has set up a website, http://www.bringbearhome.com/ where you can read more or leave tips if you have any information.

”Somebody came and picked him up and took him somewhere,” LeLanie (photo, right) theorizes. “I believe we’ll get an answer someday. Somebody knows.” The family has set up a website, http://www.bringbearhome.com/ where you can read more or leave tips if you have any information.

Melanie Aviso Bactad, 24, is a young mother. “It seems every family in Indian country has a female relative who has gone missing or been murdered,” she says. “How do you find hope when the process seems so bleak?”

But she resolves, “I want to arm my child with knowledge, not with fear…We are strong and resilient people who do make a difference in this world.”

Deanna Willis, a Kumeyaay nation member from San Pasqual, says spreading awareness is important. She is working to educate students and hopes to engage youths through social media to in turn, engage tribal leaders on the issue. “Our youth are our future,” she states.

Tiara Miller (left) from Mosques Against Trafficking explained that the average age targeted by traffickers is 14 to 15. There are women traffickers as well as men, and victims can be boys or girls The predators target troubled youths by offering compliments and gifts, then luring them to meetings at a park or mall before inviting them to parties, where the victims may be plied with drugs or alcohol.

Tiara Miller (left) from Mosques Against Trafficking explained that the average age targeted by traffickers is 14 to 15. There are women traffickers as well as men, and victims can be boys or girls The predators target troubled youths by offering compliments and gifts, then luring them to meetings at a park or mall before inviting them to parties, where the victims may be plied with drugs or alcohol.

Trafficking is now a billion dollar industry – larger than guns or drugs, Lopez notes. “Our children are in the black market.”

Deanna Willis (photo, right), a Kumeyaay from San Pasqual, explained that compromising photos are taken, or teens may be pushed to text nude images. Photos are then used to blackmail the victims; traffickers threatens to send the photos to parents, friends and schools to coerce their young victims into sexual slavery. They use kids to lure other kids on school campuses and often use online games and fake profiles on social media Victims are often raped and tattooed, forced to steal or commit other crimes.

Deanna Willis (photo, right), a Kumeyaay from San Pasqual, explained that compromising photos are taken, or teens may be pushed to text nude images. Photos are then used to blackmail the victims; traffickers threatens to send the photos to parents, friends and schools to coerce their young victims into sexual slavery. They use kids to lure other kids on school campuses and often use online games and fake profiles on social media Victims are often raped and tattooed, forced to steal or commit other crimes.

Feeling trapped and traumatized, some wind up committing suicide

If you are approached or see the warning signs of trafficking, speak up Urge kids to confide in a family member and report the activity to law enforcement. Willis urges anyone who has escaped from traffickers to “get as far away as possible, so the predator can’t find you.”

Dr. Cahuilla Red Elk, a tribal elder, praised those who shared their painful stories at the conference. “When you speak up like you have, and you cry,” she said, “people listen to you.”

Lopez offered practical advice for those experience domestic violence, such as how to obtain a restraining order to keep a batterer away and avoid eviction. She reminded moms not to take children out of state without a minor consent travel form to avoid being charged with kidnapping. She also warned not to allow a father to take children to countries that are not members of the Hague Convention (currently Bolivia, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Cuba and the Dominican Republic) because if he decides to stay their with the children, the mother has no rights to get her children back and no access to court systems in those countries

Lopez offered practical advice for those experience domestic violence, such as how to obtain a restraining order to keep a batterer away and avoid eviction. She reminded moms not to take children out of state without a minor consent travel form to avoid being charged with kidnapping. She also warned not to allow a father to take children to countries that are not members of the Hague Convention (currently Bolivia, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Cuba and the Dominican Republic) because if he decides to stay their with the children, the mother has no rights to get her children back and no access to court systems in those countries

Victims of domestic violence can get help by calling the national domestic violence hotline at 1-800-VICTIMS (842-8467).

Sexual assault survivors can call 1-800-656-HOPE (4673)

Lopez says police often act in prejudicial ways when a native girl or woman goes missing. Police may ask if the missing female is on drugs, with a man, or is a runaway.

“If you say runaway, police won’t act,” Lopez advises. “It’s less paperwork than for a missing person.”

Another problem is lack of media coverage. Only a small fraction of all missing or murdered indigenous person cases nationally are ever reported in the media, in part because police often fail to notify the press. So Lopez urges family members of those gone missing to get the word out in any way that they can, adding, “Sometimes Facebook and Instagram are all the news we have.”

She’s also on a mission to bring a class to San Diego County for those who want to become domestic violence counselors. It takes 40 hours of certification to work in a shelter or on a hotline. When Lopez asked how many in the audience would be interested in taking the class, many hands shot up.

She’s also on a mission to bring a class to San Diego County for those who want to become domestic violence counselors. It takes 40 hours of certification to work in a shelter or on a hotline. When Lopez asked how many in the audience would be interested in taking the class, many hands shot up.

She showed a slide which reads, “When women like us rise above certain incidents and decide to heal ourselves, our insistence on joy is a threat to those who devalued us.”

San Diego has the following missing indigenous person cases, as well as unsolved deaths and unidentified remains believed to be Native American or Alaskan Native people. Below are their stories. To find full details on all of these local missing and murdered people, click here.

MISSING INDIGENOUS PERSONS IN SAN DIEGO COUNTY

Elijah Runningbear Diaz (left)

Elijah Runningbear Diaz (left)

Missing since Oct. 1, 2015, he was last seen at his El Cajon home by his mother. He has a bear claw tattoo on his inner left forearm. He was on insulin and had been in a wheelchair due to a foot problem shortly before he went missing.

http://charleyproject.org/case/elijah-runningbear-diaz

Joseph L. Scott (right)

Joseph L. Scott (right)

Reported missing in November 2009 when he did not collect his Christmas bonus from the tribal hall in Pala, he wore his hair in a ponytail, had a bald spot, and green eyes. He was around 60 years old when last seen.

Joseph Victor Canul Jr. (left)

Joseph Victor Canul Jr. (left)

After coming to San Diego from Seattle in April 2007, he was never heard from again. Biracial with black and brown eyes, he was 42 years old when he went missing and may have gone back to Seattle or to Juneau, Alaska, where he was raised.

http://charleyproject.org/case/joseph-victor-canul-jr

Jeffery Paul Bohl (right)

Jeffery Paul Bohl (right)

Last seen at his home in Pauma Valley on Feb. 27, 2005, he was wearing a black sweatshirt, black T-shirt and blue jeans. He is of American Indian, Alaska native and Philipino heritage with black hair and brown eyes, weight 301 pounds.

https://oag.ca.gov/missing/person/jeffery-paul-bohl

Elaina Eugenia Rivera

Elaina Eugenia Rivera

Elaina, circa 1987; Age-progression to age 42 (circa 2016)

Last seen in the 1400 block of Mussey Grade Road on June 26, 1987, she was 13 years old when she disappeared. She was 5 ft. 5 at the time with a small scar on the right side of her upper lip, a burn scar on her forearm, and broken front teeth.

http://charleyproject.org/case/elaina-eugenia-rivera

Mel Gean McGregor, a.k.a. Bianca Whitewing

Mel Gean McGregor, a.k.a. Bianca Whitewing

Last seen Sept. 14, 2015 in Chula Vistas, she had tattoos on her right shoulder, left arm and hand, as well as a scar near her left eye. She was 50 years old when she disappeared and may use the name Biana Whitewing; she has also been known as Bianca Jean Herrada.

http://charleyproject.org/case/mel-gean-mcgregor

UNIDENTIFIED NATIVE AMERICAN OR UNKNOWN ETHNICITY REMAINS FOUND IN THE SAN DIEGO REGION

The follow are listed in the NamUs database.

A human skull was found June 9, 2017 by a transient in a marsh near Plaza Bonita Rd. in Bonita. The deceased is estimated to be 20-40 years old with Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native ethnicity. NamUs #UP53451

A skull found by a hiker March 14, 2016 in the Otay Mountain are of Jamul is estimated at 20-40 years and believed to be male. Old and of Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native heritage. There was evidence of past reconstructive surgery after facial trauma. NamUs#UP53849

A body found on April 29, 2012 in the Trestles Wetland Preserve in San Clemente by workers cutting palm trees. The deceased was estimated at 30-50 years old, bald, and of Caucasian, Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native ethnicity. NamUs #UP55199

Partial skeletal remains of a woman were found April 18, 2011 in Boulevard, California on the Campo Indian reservation by a person clearing vegetation along the west side of Church Road. She is believed to have been younger than age 40 and of Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native heritage. NamUs #UP55217

A fire prevention officer with the Campo Reservation found a bone on July 7, 2010 while cutting brush alongside Church Rd. The bone was from an adult male of uncertain race/ethnicity, who is estimated to have been around 5’5 to 5’6 inches tall. NamUs #UP55243

A decomposing body of a female around 4 ft. 10 inches tall with long, thick brown hair was found August 30, 2001 along Church Rd. near State Route 94 in a remote, open area in Campo. NamUs #UP55985

A femur bone belonging to a man around age 40 was found on January 2, 2005 in Coyote Canyon in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park by a group of off-road vehicle recreational enthusiasts. The deceased is believed to have been between 5 ft. and 5 ft. 5 inches tall, of Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native descent. NamUs #UP55712

Partial burned human bone fragments were discovered November 6, 2009 by archaeologists surveying rural Dulzura for Native American remains and artifacts. The male remains are of uncertain age and ethnicity. NamUs #UP55244

UNSOLVED DEATHS

Sequoyah Callahan Galvin of the Soboda Band of Luiseno Indians went missing on December 31, 2016 in Valley Center. On July 13, 2018, he was found shot in the head and killed in the northwest Hemet community of Stoney Mountain Ranch.

Shawn “Lone Wolf” Christman, aka Coyote (left), of the Santa Ysabel Reservation went missing in 1993. His body washed ashore in Lake Michigan in June 1993 and he was buried in Chicago as an unidentified John Doe in December 1994. After nearly 26 years, a detective following up on the missing person case cross-checked fingerprints and Christman’s body was finally identified.

Shawn “Lone Wolf” Christman, aka Coyote (left), of the Santa Ysabel Reservation went missing in 1993. His body washed ashore in Lake Michigan in June 1993 and he was buried in Chicago as an unidentified John Doe in December 1994. After nearly 26 years, a detective following up on the missing person case cross-checked fingerprints and Christman’s body was finally identified.

Comments

Sovereign nations?

Tribal law enforcement is limited in some jurisdictions.

California is better than most. But in some states tribal police are prohibited from arresting non-Natives who commit crimes on the reservation; that would be up to outside law enforcement agencies and in some areas they aren't doing an adequate job. Tribal courts in some areas cannot prosecute non-Natives either, so they are the mercy of the outside justice system which doesn't always work very well.

This is slowly changing; more and more areas are granting broader powers to tribal law enforcement and courts, but not all. Also some tribal governments are more effective than others.

Some areas have cooperative agreements with law enforcement that work both ways, ie, a Sheriff could come onto the reservation to arrest a Native American wanted for a crime elsewhere and tribal authorities could try an outsider who committed a crime. So there are various rules in various places instead of full federal protections everywehre.

:'-(