The following article on the buildings that burned during civil unrest in La Mesa appeared in the Fall Issue of Lookout Avenue, newsletter of the La Mesa Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. To learn more about the Greater La Mesa area’s history, visit lamesahistory.com or their Facebook site.

The following article on the buildings that burned during civil unrest in La Mesa appeared in the Fall Issue of Lookout Avenue, newsletter of the La Mesa Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. To learn more about the Greater La Mesa area’s history, visit lamesahistory.com or their Facebook site.

By James D. Newland, La Mesa Historical Society

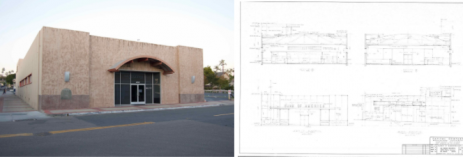

Photo, above: First National Trust/Piggly Wiggly Building (1942), 4767 Palm Avenue, Edmund Dunn, master builder. Randall Lamb Engineering, rehab designers. May 2020.

September 20, 2020 (La Mesa) - Almost immediately after the tragic destruction of three recognizable commercial buildings on the evening of May 30th-31st, the Society and myself began to receive requests for information on the history of the three iconic architectural staples of downtown La Mesa’s historic landscape. Upon gathering the stories of each of these prominent, long-standing commercial buildings it became clear that they had unrecognized historical connections to each other, as well as with other buildings and sites within downtown’s contextual history.

Photo, right: Imperial Savings/Chase Bank (1973), Richard George Wheeler, architect. 4791 Spring Street, May 2020.

Photo, right: Imperial Savings/Chase Bank (1973), Richard George Wheeler, architect. 4791 Spring Street, May 2020.

For more recent La Mesa residents the presence of these three commercial buildings, the First National Bank/Piggly Wiggly Market (1942) at 4757 Palm, the Imperial Savings/Chase Bank (1973) at 4791 Spring, and the Southern California First National/Union Bank (1974) at 4771 Spring may have had little personal connection. Unless you were a customer of the two banks or a client to the Randall Lamb engineering firm that had masterfully rehabilitated that Palm Avenue building, you may not have ever gone inside any of them.

Photo, below: Southern California First National/Union Bank (1974), 4771 Spring Street, Russell Forster, architect. May 2020.

Personally, I had only been inside the Randall Lamb building when the Society had partnered to put a historic photo plaque on the building some five years ago. And although I had driven and walked by the other two bank buildings thousands of times and had taken photographs of them just weeks before as part of our City Historical Survey update efforts, I never had a reason to go inside either building. Yet, they reflected the Modern interpretation of bank architecture from two renown San Diego architects that were clearly reminiscent of their early 1970s pedigree.

The Banks of La Mesa: Icons of Community Growth and Strength

Having researched local bank history back in the 1990s including El Cajon’s pioneering Cuyamaca Bank buildings (1907 and 1922) once located on the southwest corner of Magnolia and Main Streets (the second building demolished for a street widening project in the mid-1990s), the history of bank architecture is one of symbolic significance. Regular bank failures in the 19th century led financial institutions to commission 20th century designs representing what their customers would perceive as both institutional stability and financial safety.

Photo, right: Bank of La Mesa/Park-Grable Investment Building (1909), Spring at Lookout, Irving Gill, architect. June 1912. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, right: Bank of La Mesa/Park-Grable Investment Building (1909), Spring at Lookout, Irving Gill, architect. June 1912. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

The Bank of La Mesa was our community’s first local bank. The Bank’s original 1909 building was located at the northwest corner of Spring and Lookout (now La Mesa Blvd.). Its California-influenced austere and cutting-edge Irving Gill design representing a “modern” forward-thinking institution for the young Progressive Era community. After the building was damaged in a 1919 fire, it was replaced by a larger and more typical “Classical” style concrete-walled building in 1921.

Photo, left: Bank of La Mesa/Bank of America Building (1921). Spring at Lookout. Circa 1940. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, left: Bank of La Mesa/Bank of America Building (1921). Spring at Lookout. Circa 1940. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

In 1926 A.P. Giannini’s San Francisco based Bank of Italy purchased and renamed La Mesa’s hometown bank. Then in 1931 they changed their name to its current moniker, the Bank of America. They continued to use this building until moving to a new bank constructed at 4719 Palm Avenue by Lemon Grove master builder Edmund Dunn in 1955. The 1921 Bank of La Mesa/Bank of America building was torn down for the Anthony’s Furniture Store construction that same year (current site of the Goodwill Store).

Photo, right: Bank of American Building (1955). 4719 Palm Avenue. Raymond Shaw, architect. Edmund Dunn, contractor. May 2020. Original Drawing from Dunn Collection, 1955. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, right: Bank of American Building (1955). 4719 Palm Avenue. Raymond Shaw, architect. Edmund Dunn, contractor. May 2020. Original Drawing from Dunn Collection, 1955. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, left: Anthony’s Furniture (1955), 8250 La Mesa Blvd. remodeled. April 2020.

Photo, left: Anthony’s Furniture (1955), 8250 La Mesa Blvd. remodeled. April 2020.

Bank of Southern California Arrives

With Southern California in the midst of another real estate and development boom in the mid-1920s another bank assembled a mixture of local and regional investors to open a branch in growing La Mesa. That was the aptly named Bank of Southern California. Formed in 1926 the new financial institution included investors from the First Trust and Savings Bank of San Diego and San Diego Trust and Savings Bank, both of which dated their origins to the 1880s. First Trust Bank President I.I. Irwin was also instituted as the initial Board president of the new La Mesa-based bank. The Bank’s directors included local East County investors J. O. Miller of La Mesa (bank manager), George Graves of El Cajon, A. F. Sonka of Lemon Grove and Mt Helix pioneer resident and developer Fred J. Hansen. In January 1927 the new Bank opened for business in a rented space across the street next to the La Mesa Drug Store.

Photo, right: Bank of Southern California (1927), 8300 Lookout Avenue. New Post Office at rear with empty lots to the south in view. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, right: Bank of Southern California (1927), 8300 Lookout Avenue. New Post Office at rear with empty lots to the south in view. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

The Bank then purchased the prominent northeast corner of Palm and Lookout (now La Mesa Blvd.), demolished the 1908 La Mesa Opera House theater building and started construction on a new $30,000 bank building in Spring 1927. The new Bank of Southern California building also featuring an addition on its Palm Avenue frontage to house a new, “modern” Post Office and additional storefronts on the Lookout Avenue side. In August 1927 their new building was open along with the new Post Office and Fred Hansen’s real estate office. This prominent building featured thick concrete walls in a Mediterranean Revival style reflective of 1920s Southern California. Today most know this as the long-standing home of Por Favor Restaurant.

The Bank quickly became a prominent member of the La Mesa Chamber of Commerce and helped finance the commercial and residential development of the community. Although the Boom of the 1920s would start to slow in late 1928, and collapse with the onset of the Great Depression, the Bank would survive the financially challenging 1930s. One of the ways they accomplished this was to merge with their larger San Diego based investment partner, the First National Trust and Savings Bank, in June 1934.

First National Trust New Modern Bank and Piggly Wiggly Supermarket

After lasting out the Depression years, San Diego’s ties to the military and aircraft industry began to pay off. With World War II underway in Europe, San Diego’s military and aircraft industry boomed, thus triggering a rapid and exponential growth known as “the Blitz Boom.” From 1939 to 1943 the County’s population would double—as would La Mesa’s. Soon any available housing or commercial space was in demand.

Photo, left: prosperous Lookout Avenue, 1929. Original Piggly Wiggly Market next to La Mesa Drug Store. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, left: prosperous Lookout Avenue, 1929. Original Piggly Wiggly Market next to La Mesa Drug Store. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Recognizing that their beautiful and sturdy concrete-walled building would not be easily expanded, and no other commercial buildings were available in the growing town of 4,000, the Bank looked to find a new building location in La Mesa. Early in 1941 First National purchased empty lots 32 and 33 in the triangular shaped Hood Tract directly north of the Bank across the alley behind the Bank/Post Office buildings. They partnered with another long-standing business, the Piggly-Wiggly Supermarket company. One of the attractions for the Piggly-Wiggly to move off its original location at 8313 La Mesa Boulevard was the fact that the new commercial property would have free off-street parking—a key element of supermarket design that would make them perfect anchors for automobile oriented suburban shopping centers.

In July 1941 First National and Piggly Wiggly announced their mutual construction projects on Palm Avenue. The $50,000 concrete-walled First National Trust bank and $15,000 masonry block supermarket represented two of the largest commercial projects undertaken in La Mesa at that time. Although both had hoped to be open by Christmas 1941, challenges in getting materials and the U.S. entry into World War II after the December 7th attack on Pearl Harbor delayed completion.

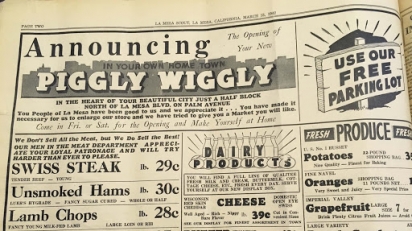

Photo, right: Piggly Wiggly Advertisement announcing new building at 4767 Palm Avenue. La Mesa Scout March 13, 1942. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, right: Piggly Wiggly Advertisement announcing new building at 4767 Palm Avenue. La Mesa Scout March 13, 1942. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

On Friday, March 13, 1942, La Mesa’s Piggly Wiggly opened its new store, touting their “free parking lot” and full service one-stop grocery store at 4767 Palm. Its Streamline Moderne style façade was considered cutting-edge for supermarket design. For southern Californians in the 1930s, the designs of notable Los Angeles architect Styles Clements’ Streamline Ralph’s stores, setting the Pre-War supermarket design standard.

One month later on Saturday April 18th 1942 First National Trust held a late afternoon open house for its new branch. Lemon Grove master builder Edmund Dunn had completed the building at 4757 Palm. The La Mesa Scout of April 17th described it glowingly:

“Modern. Handsome. Complete. As fine a banking house as any city in the country can boast, and large enough to take care of the needs of this growing community for years to come.”

Photo, left: Grand Opening article, First National Trust and Savings Bank, La Mesa Scout April 17, 1942. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, left: Grand Opening article, First National Trust and Savings Bank, La Mesa Scout April 17, 1942. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

The Scout remarked on the modern features in design, furnishing and mechanical equipment. Noting that “The handsome interior combines the ideas of bankers, architects, artists and decorators of sound, lighting and air conditioning engineers in foreseeing…the comfort and convenience of bank patrons.” The new lighting providing “daylight” throughout and the latest in air conditioning to control temperature and humidity to insure comfort year-round in the windowless building.

Dr. Roy Campbell, reverend of La Mesa’s Congregational Church, and many times Mt. Helix Easter Services pastor, wrote in his May 8, 1942 Scout column a few weeks later of the impressive and modern building. Campbell requested that all who could, should visit the building. He described it glowingly:

“It is shadowless and noiseless. The lighting is like sunshine. There are no windows. And the new fangled walls absorb noise. Fancy that—drink it up like a sponge does water.”

In the same edition, one of La Mesa’s most famous local residents added a similar testimonial. Carrie Jacobs Bond, noted poet, author and Grossmont resident wrote a letter to the First National Bank manager, referencing a promotional booklet that the bank had produced with some of her verse about La Mesa.

“I am so perfectly delighted with the “Jewel of the Hills,” and I have never seen such a lovely picture of my little spot. I deeply appreciate your honoring me by putting my little verse in the magazine. I am so proud of La Mesa.”

For the next twenty years the First National Bank and Piggly Wiggly represented the growing, modernizing suburban city. Although Piggly Wiggly would later be bought out by Safeway Stores and close their 4767 Palm location in 1960 (to move to its new building at 4630 Palm—now home to Sprouts) the old storefront continued as a market into the 1960s. First National Trust continued to use the site up into the early 1970s as well. Located just one block north of La Mesa Blvd. and one block west of Spring Street, bounded by Orange Avenue’s eastern terminus, its location was as central La Mesa as could be for a local bank and commercial building.

Downtown Challenges Bring Plans of Change

Photo, right: Sanborn Map, La Mesa Sheet 6 crop, 1961 Series. This circa 1959 map shows Orange Avenue’s eastern block and the commercial buildings that would be removed in 1973 to make way for redevelopment. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, right: Sanborn Map, La Mesa Sheet 6 crop, 1961 Series. This circa 1959 map shows Orange Avenue’s eastern block and the commercial buildings that would be removed in 1973 to make way for redevelopment. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

As the City continued its exponential suburban growth through the 1950s and 1960s, including the annexation of today’s City north of Interstate 8 and the Grossmont Center and Fletcher Hills areas to the northeast, downtown’s city center and commercial focus was affected. Up to 1958 La Mesa City Hall sat at the northeast corner of Spring and Orange. With that important civic building located there, the entire block between Spring, Orange, Palm and Allison was fully developed with commercial and retail buildings.

The first big change was the development of the City’s Civic Center on Allison Avenue, west of Spring (the current location) in the late 1950s. When the new city hall opened there in 1958 (the only building from the 1950s left there today), along with Grossmont Center Regional Mall opening in October 1961, downtown La Mesa’s fifty-year reign as the commercial hub of the greater La Mesa area was being questioned and challenged.

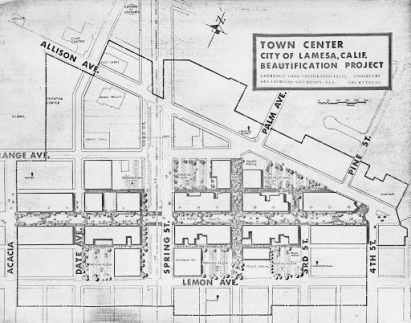

Photo, left: La Mesa Town Center Project Concept Map c1960. DesLaurier Collection, La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, left: La Mesa Town Center Project Concept Map c1960. DesLaurier Collection, La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

The City and La Mesa Chamber of Commerce spent significant time, effort and funds toward a new plan for revitalizing the historic commercial core. The Town Center project, led by La Mesa architect Robert DesLauriers considered significant changes for downtown including a pedestrian mall closing portions of La Mesa Blvd and Palm Avenue as well as other investment to help the long-standing businesses compete with the new regional shopping mall and its Marston’s Department Store and Montgomery Wards’ anchor stores. With the City Council’s surprising 1966 rejection of the five year plus Town Center Plan effort, the City would turn to a new plan for redevelopment of downtown in the early 1970s.

Redevelopment East of Spring Street

Most La Mesans can recognize the City’s major redevelopment efforts of the 1970s and 1980s in the properties west of Spring Street including the La Mesa Springs Shopping Center and Village Plaza Housing Tower and Trolley Station that cleared the north side of La Mesa Blvd. to Acacia Avenue and out through to University Avenue. Those redevelopment projects resulted in the closure of most of Orange Avenue west of Spring Street.

Although the La Mesa Downtown Merchants Association initially were opposed to the City’s Redevelopment Project, they changed their position when concerns for additional parking and significant investment were addressed in the plans. In June 1973 the City Council approved beginning the City’s 45-acre downtown Redevelopment District planning effort.

One of the City’s earliest downtown “redevelopment inspired” projects included two significant new buildings east of Spring Street. Following City Attorney’s Lee Knutson’s activating the City’s redevelopment function in early 1973, the above-mentioned block (Block C, La Springs Subdivision) between Spring, Orange, Palm and Allison that held the former City Hall and other business buildings was ready for new uses. Soon after the buildings on Block C were razed. It was then that two long-standing La Mesa banking institutions interested in creating new, modern homes for their banks moved to re-develop the block.

Imperial Savings/Chase Bank (4791 Spring Street)

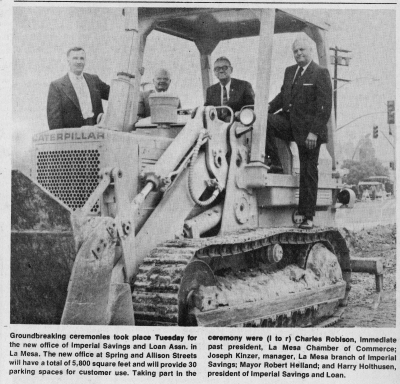

Photo, right: groundbreaking for Imperial Savings and Loan Bank, 4791 Spring Street. June 28, 1973 La Mesa Scout. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, right: groundbreaking for Imperial Savings and Loan Bank, 4791 Spring Street. June 28, 1973 La Mesa Scout. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

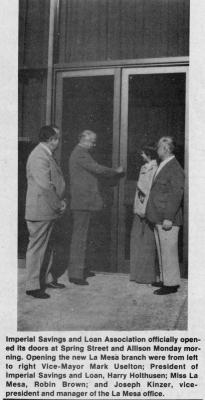

Imperial Savings and Savings Loan Association was the first to move forward. They purchased the property on the southeast corner of Spring and Allison. In late June, flanked by Mayor Robert Helland and La Mesa Chamber of Commerce past president Charles Robison, Imperial Savings President Harry Holthusen (who lived in Eastridge) and branch manager Joseph Kinzer held the ceremonial groundbreaking for their new building.

Imperial Savings and Loan had its start locally in 1946 under the name of La Mesa-El Cajon Savings & Loan. Their original building was located at 8347 La Mesa Blvd, southwest corner of Third Street (now site of First Republic Bank). In 1958 they changed their name to Southland Savings & Loan to reflect their growth beyond our local area. After several mergers and acquisitions the savings and loan became Imperial Savings with branches in over 30 cities throughout southern California by 1973. Many remember film and “Green Acres” television star Eddie Albert as their long-standing spokesperson.

During this period of growth, Imperial Savings had retained the noted San Diego architectural firm of Richard George Wheeler Associates, Wheeler’s firm having designed the new Parkway Plaza branch in El Cajon (built by La Mesa contractor Riha Construction) and the Chula Vista branch for Imperial Savings, both in 1972. Wheeler, whose father was noted San Diego master architect William Henry Wheeler, had grown his firm into one of the largest and most prolific in post-war San Diego. The firm’s portfolio included custom residences, tract homes, commercial, retail, religious, government and institutional commissions. Some of his most notable work was for notorious San Diego businessman C. Arnholt Smith, including several of his U.S. National Bank branches, as well as for First National Trust and Savings Bank.

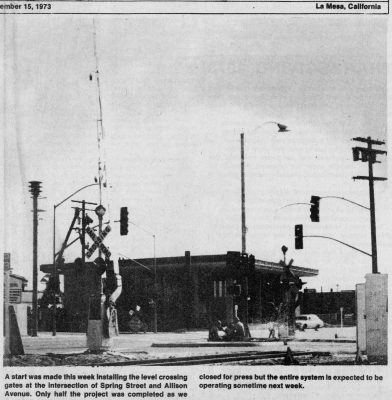

Photo, left: Imperial Savings and Loan under construction. La Mesa Scout November 15, 1973

Photo, left: Imperial Savings and Loan under construction. La Mesa Scout November 15, 1973

Wheeler’s design for the new 5,800 square foot Imperial Savings La Mesa branch took advantage of its corner location to face out toward the heavy traffic of Spring Street. After the June 1973 groundbreaking the building was completed in December 1973, formally opening shortly before Christmas. Imperial Savings then held a special week-long Grand Opening celebration starting on January 2, 1974. The opening featured free gifts including an “energy-saving wheel” to help residents save money during the height of the 1973 oil embargo inspired “energy-crisis.”

Photo, right: open for business. La Mesa Scout December 20, 1973. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Imperial Savings continued to grow with the region. In the 1980s the savings and loan merged, went national and changed its name several times. In 1990 however, as result of the national savings and loan crisis, Imperial Federal Savings Association failed, was placed in receivership, and reorganized. The San Diego based company moved its headquarters from San Diego in 1995. After various reorganizations, mergers and purchases Chase Bank took over the assets including the La Mesa branch building.

Southern California First National Bank/Union Bank (4771 Spring Street)

Photo, left: Imperial Savings Grand Opening, La Mesa Scout January 10, 1974. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, left: Imperial Savings Grand Opening, La Mesa Scout January 10, 1974. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

With the opportunity to once-again update their bank building in 1973, the renamed Southern California First National Bank at 4757 Palm purchased the parcel across the street that had included the former City Hall and the recently closed portion of east Orange Avenue. First National Trust and Southern California First National having previously merged into a financial institution with 69 branches in San Diego, Orange and Los Angeles counties.

In November 1973 First National’s La Mesa branch manager Ken Trent and key bank officials broke ground for a new 6,850 square foot, $1 million building to replace their 1942 building. Trent noted that the new office would provide significant customer-serving amenities including eight teller stations, four drive-through kiosks and 49 parking spaces, commenting that “our customers will appreciate the conveniences.”

Photo, right Southern California First National Bank groundbreaking, November 1, 1973 La Mesa Scout. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, right Southern California First National Bank groundbreaking, November 1, 1973 La Mesa Scout. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Similar to Imperial Savings, First National had contracted the services of one of San Diego’s notable Modernist architects and artists, Russell Forester. Forester, a graduate of La Jolla High, had begun his architectural career as a draftsman with local Modernist icon Lloyd Ruocco before opening his own architectural design office in 1948. After studying at the Chicago Institute of Design in 1950-51, where he was influenced by the work of Mies Van Der Rohe’s International and New Bauhaus styling, he returned to San Diego. His early work was noted for these “Miesian” influences. In 1951 Forester got his most noted and prolific commission for Bob Peterson’s Jack-In-The-Box drive-through restaurants. The first of these automobile-influenced “food dispensing” buildings being located at 63rd and El Cajon Boulevard. Forester would eventually design some 200 Jack-In-The-Box buildings for Peterson’s Foodmaker Corporation.

Photo, left: Russell Forester model for Kearny Mesa Branch, similar to La Mesa branch design. San Diego Union, September 9, 1971. Author’s collection.

Photo, left: Russell Forester model for Kearny Mesa Branch, similar to La Mesa branch design. San Diego Union, September 9, 1971. Author’s collection.

Among Forester’s voluminous and impressive portfolio of Modernist masterpieces are the half dozen banks for Southern California First National Bank in the early 1970s. The first of these new buildings, which were expected “to establish a stronger systemwide identity” for the bank, being the Kearny Mesa branch on Clairemont Mesa Boulevard in 1971. Forester’s modular bank model featured a precast, sandblasted design to allow for size and floor variations depending on the specifics of the site. Subsequently the La Mesa branch was very similar to the Kearny Mesa building with a Contemporary style using wood and glass to make the building more approachable than the older austere but sturdy style banks. In addition, the La Mesa branch would include an open-air atrium to emphasize a connection with the indoor and outdoor landscaping along with bright purple, orange, red and blue interior colors.

Photo, right: Opening Day, Southern California First National Bank, 4771 Spring Street, May 9, 1974 La Mesa Scout. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

Photo, right: Opening Day, Southern California First National Bank, 4771 Spring Street, May 9, 1974 La Mesa Scout. La Mesa Historical Society Archives.

The new Southern California First National Bank opened in May 1974. Advertisements noted the new branch’s benefits of more free parking, drive-up lanes, faster service and evening hours for the drive-throughs (kiosks open to 7:30pm!). (Many may not remember that “bankers hours” used to make banking a mid-day-only event—this drive-up service being a precursor to the ATMs and 24 hour on-line banking we take for granted today).

Southern California First National Bank would merge with California First Bank of San Francisco in 1975. In 1988 California First acquired Union Bank of California and changed its name in 1996. The Union Bank in Casa de Oro is also a Russell Forester design that opened in 1975. Russell Forester would set aside his architectural practice in 1976 to focus on his artwork, which can be found in many of his buildings.

Adaptive Use for 4767 Palm

After Southern California First National moved into their new building at 4771 Spring Street, they leased out their old building. For a time, San Diego County used the concrete-walled building for records storage. In the 1980s La Mesa Appliance rented out the property for their retail operations.

Photo, left: Randall Lamb Building, 4767 Palm Avenue, May 2020.

Photo, left: Randall Lamb Building, 4767 Palm Avenue, May 2020.

In the 2010s Randall Lamb engineering purchased the 4757-67 building. They undertook a well-done historic rehabilitation adaptive use project. The project providing the long-standing San Diego based engineering firm a new home while giving the beautiful and impressive 1942 building new life. In 2015 the Historical Society, along with our La Mesa Rotary Club partners recognized the building’s important status with a historical photo plaque.

Interconnected Histories

The individual histories of these three buildings and their commercial and retail tenants, aside from their tragic and shared demise, provide a fascinating view into the small-town character of downtown La Mesa’s business and commercial histories. Although some observers may only have seen the destruction of two large corporate bank branches, the origins of both of those two buildings and their tenants had ties as original local financial institutions as well as being works of notable San Diego commercial architects.

The third building, Palm Avenue’s First National Trust/Randall Lamb building, not only was directly associated with its next home, the also destroyed Union Bank, but can trace its origins down the street to the 1927 Bank of Southern California. It was doubly painful to lose this classic La Mesa building, especially considering its impressive rehabilitation and re-vitalization by Randall Lamb engineering for a new and successful reuse.

Hopefully this short history of how each of these buildings’ integrated local pedigree, both in association with long-standing businesses and other existing sites and buildings in our local downtown, will remind us all of how such losses to our collective historical landscapes can be more community-wide than they may initially appear. We can also only hope that whatever comes next for these properties can have a similar imprint and impact for La Mesa’s landscape future.

Comments

Piggly Wiggly

There was one in Lemon Grove too. I believe it was in the building now occupied by LG Bakery.

Alao there was a market on the corner of Broadway and Massachuttes Ave. A very simple wood building, all the produce and other items were from local farms and dairies.