by Laura A. Lewis (Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2012, 370 pages)

by Laura A. Lewis (Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2012, 370 pages)

Book Review by Dennis Moore

November 29, 2012 (San Diego) -- Before reading Chocolate and Corn Flour, I did not know that there was such a thing as a "Black" Mexico.” Having lived in Tijuana, Mexico for a number of years and visited a number of Mexican cities, such as Cancun and Rosarito Beach, this book comes as a revelation to me.

Laura A. Lewis, Professor of Anthropology at James Madison University, and the author of Hall of Mirrors: Power, Witchcraft, and Caste in Colonial Mexico, has written a scholarly and thought provoking book about the history and culture of Mexico; Chocolate and Corn Flour: History, Race, and Place in the Making of "Black" Mexico. The author has indicated that “Chocolate and Corn Flour” is the literal translation of the word champurrado, a chocolate based atole. She further states that a local woman once used it to describe to her the marriage of a moreno man and an Indian woman.

Located on Mexico's Pacific coast in a historically black part of the Costa Chico region, the town of San Nicolas has been identified as a center of Afromexican culture by Mexican cultural authorities, journalists, activists, and foreign anthropologists. The majority of the town's residents, however, call themselves morenos (black Indians). In Chocolate and Corn Flour, the author explores the history and contemporary culture of San Nicolas, focusing on the ways that local inhabitants experience and understand race, blackness, and indigeneity, as well as on the cultural values that outsiders place on the community and its residents.

Drawing on more than a decade of fieldwork, Lewis offers a richly detailed and subtle ethnography of the lives and stories of the people of San Nicolas, including community residents who have migrated to the United States. San Nicoladenses, she finds, have complex attitudes toward blackness - as a way of identifying themselves and as a racial and cultural category. They neither consider themselves part of an African diaspora nor deny their heritage. Rather, they acknowledge their hybridity and choose to identify most deeply with their community. The author points out in her book that the ancestors of most San Nicoladenses were African and African-descent slaves and free persons, referred to as blacks (negros) and mulattoes (mulatos) in colonial texts. She further indicates that because of demographics and social interactions between blacks and Indians, mulattoes in colonial Mexico were frequently of black and Indian descent (Motta 2oo6: 121; also Lewis 2003: 74 - 78). Mexico's history of slavery - in full force for about 150 years - has been amply documented, according to Lewis, but she highlights a few points in Chololate and Corn Flour, both general and specific. Lewis states that until 1700, with the de facto end of the Mexican slave trade, Mexico hosted one of the largest black and mulatto populations in the Americas. She says that Spaniards brought slaves directly from West and Central Africa during this period, but they also brought some to Spain to Hispanicize and Christianize them before transport to the New World.

Drawing on more than a decade of fieldwork, Lewis offers a richly detailed and subtle ethnography of the lives and stories of the people of San Nicolas, including community residents who have migrated to the United States. San Nicoladenses, she finds, have complex attitudes toward blackness - as a way of identifying themselves and as a racial and cultural category. They neither consider themselves part of an African diaspora nor deny their heritage. Rather, they acknowledge their hybridity and choose to identify most deeply with their community. The author points out in her book that the ancestors of most San Nicoladenses were African and African-descent slaves and free persons, referred to as blacks (negros) and mulattoes (mulatos) in colonial texts. She further indicates that because of demographics and social interactions between blacks and Indians, mulattoes in colonial Mexico were frequently of black and Indian descent (Motta 2oo6: 121; also Lewis 2003: 74 - 78). Mexico's history of slavery - in full force for about 150 years - has been amply documented, according to Lewis, but she highlights a few points in Chololate and Corn Flour, both general and specific. Lewis states that until 1700, with the de facto end of the Mexican slave trade, Mexico hosted one of the largest black and mulatto populations in the Americas. She says that Spaniards brought slaves directly from West and Central Africa during this period, but they also brought some to Spain to Hispanicize and Christianize them before transport to the New World.

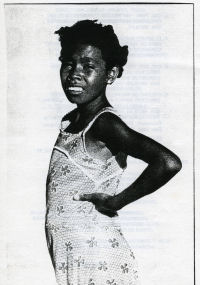

A picture of a La Cuculusta (The Kinky-Haired Girl) that Cuaji culture workers produced for the First Traditional fair in San Nicolas in 1998, which outsiders organized, insult community members' sensibilities ("She hardly looks like anyone here," remarks one of the local inhabitants; while claiming that she appeared to have "corn dough in her teeth"). Perhaps this is where the notion of Chocolate and Corn Flour came from. Also, a further denigration of the black race, universally.

A picture of a La Cuculusta (The Kinky-Haired Girl) that Cuaji culture workers produced for the First Traditional fair in San Nicolas in 1998, which outsiders organized, insult community members' sensibilities ("She hardly looks like anyone here," remarks one of the local inhabitants; while claiming that she appeared to have "corn dough in her teeth"). Perhaps this is where the notion of Chocolate and Corn Flour came from. Also, a further denigration of the black race, universally.

It is interesting to note in the author's book that many of the San Nicoladenses, morenos or black Indians, have immigrated to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. As a matter of fact, there is a particular "Waughtown" area in Winston-Salem that when Latinos started moving in, blacks started moving out. Blacks now call it "little Mexico." Lewis makes many such racial observations in her book. She suggests in Chocolate and Corn Flour that there is an inherent racial tension between blacks and Latinos, separate and apart from the dominant white culture. Race and color can be such a divisive and misunderstood concept. Vidal Cortez stated to me in regard to Lewis’ book: “As an AfroMestizo (Mexican origin) born in the U.S., I find it troubling that African Americans or anyone else other than AfroMestizos, Morenos, or AfroMexicanos would write any type of literature regarding customs, traditions, ‘life of Mexican, Colombian, Puerto Rican, or any other AfroMestizo born from Spanish colonialism ... I would never consider telling the world of African American struggle, customs, beliefs, no matter how many books I’ve read or number of people I’ve interviewed – knowing that people with cancer does not make me an authority on life of those with cancer – Mexico and her peoples that are able to trace their roots back to colonial times are almost all AfroMestizo (being of all 3 colonial bloods) and some have a distinct African phenotype while most appear more indigenous however make no mistake, a few hundred years of miscegenation has produced our beautiful mix of bloods.” Clearly, Mr. Cortez takes exception to this well written and scholarly assessment by Lewis.

Perhaps the most profound observation made by Lewis in her book as it regards San Nicolas, is the two-day ritual performance there for Independence Day (September 15) called La America or Los Apaches. Lewis states: "In San Nicolas, La America follows the template of a conquest play, but it is really about reconquest (independence) as Indians take territory back from Spaniards, thereby freeing the Mexican nation from its captors. On the surface the play seems straightforward: Indians defeat Spaniards and Mexico becomes an independent nation. But it also contains a hidden transcript as morenos align with the Indian victors and thus work themselves into a nation that has historically excluded them. It is now whites who are now written out of the nation as black Indians take its center. Rather than highlightening the tensions between marginalized peoples and a conflated nation-state (Cohen 1994:150), La America assimilates blackness to Indiananess as it effects a split between the nation, feminized and black Indian, and the state, which is masculinized and white. Thus the state and the nation are raced, gendered, and split apart."

Perhaps the most profound observation made by Lewis in her book as it regards San Nicolas, is the two-day ritual performance there for Independence Day (September 15) called La America or Los Apaches. Lewis states: "In San Nicolas, La America follows the template of a conquest play, but it is really about reconquest (independence) as Indians take territory back from Spaniards, thereby freeing the Mexican nation from its captors. On the surface the play seems straightforward: Indians defeat Spaniards and Mexico becomes an independent nation. But it also contains a hidden transcript as morenos align with the Indian victors and thus work themselves into a nation that has historically excluded them. It is now whites who are now written out of the nation as black Indians take its center. Rather than highlightening the tensions between marginalized peoples and a conflated nation-state (Cohen 1994:150), La America assimilates blackness to Indiananess as it effects a split between the nation, feminized and black Indian, and the state, which is masculinized and white. Thus the state and the nation are raced, gendered, and split apart."

Interestingly, in this annual play, blacks as such are not obviously present in a ritual that commemorates freedom in a historically black region of Mexico, indeed the emancipation of blacks after independence is not mentioned at all, raises a number of troubling questions. The author further points out in Chocolate and Corn Flour: "Because there are no African survivals or even blacks in La America, morenos dressed up as Indians stand for Mexicans in a country that, as morenos repeatedly insist, has always been free, but one they know also rejects blackness. Indeed, for San Nicoladenses, even runaway slaves cease to be black once they reach land, where they mix with people already mixed. Unlike Indianness and whiteness, blackness has no symbolic or capital value in Mexico. The ritual therefore continues to efface blackness from the nation. This effacement repeats in coastal discourses centered on black's alleged violence and laziness, and, from the perspective of San Nicoladenses, also in culture worker's stress on blacks' differences from other Mexicans because of their Africanness, related in both direct and indirect ways to a heritage culture workers essentialize in 'blood,' an issue addressed in the following chapters."

Interestingly, in this annual play, blacks as such are not obviously present in a ritual that commemorates freedom in a historically black region of Mexico, indeed the emancipation of blacks after independence is not mentioned at all, raises a number of troubling questions. The author further points out in Chocolate and Corn Flour: "Because there are no African survivals or even blacks in La America, morenos dressed up as Indians stand for Mexicans in a country that, as morenos repeatedly insist, has always been free, but one they know also rejects blackness. Indeed, for San Nicoladenses, even runaway slaves cease to be black once they reach land, where they mix with people already mixed. Unlike Indianness and whiteness, blackness has no symbolic or capital value in Mexico. The ritual therefore continues to efface blackness from the nation. This effacement repeats in coastal discourses centered on black's alleged violence and laziness, and, from the perspective of San Nicoladenses, also in culture worker's stress on blacks' differences from other Mexicans because of their Africanness, related in both direct and indirect ways to a heritage culture workers essentialize in 'blood,' an issue addressed in the following chapters."

Chocolate and Corn Flour is an insightful and remarkable study of color and race, with all its subtleties and implications, by a Professor of Anthropology that has obviously conducted many years of research on the subject. It is a book that I highly recommend.

Dennis Moore is the book review editor for SDWriteway, an online newsletter for writers in San Diego. He has been a freelance contributor to the Baja Times Newspaper in Rosarito Beach, Mexico and the San Diego Union-Tribune Newspaper. He is also the author of a book about Chicago politics; "The City That Works: Power, Politics and Corruption in Chicago. Mr. Moore can be contacted at contractsagency@gmail.com or you can follow him on Twitter at: @DennisMoore8.

Dennis Moore is the book review editor for SDWriteway, an online newsletter for writers in San Diego. He has been a freelance contributor to the Baja Times Newspaper in Rosarito Beach, Mexico and the San Diego Union-Tribune Newspaper. He is also the author of a book about Chicago politics; "The City That Works: Power, Politics and Corruption in Chicago. Mr. Moore can be contacted at contractsagency@gmail.com or you can follow him on Twitter at: @DennisMoore8.

Comments

"MESTIZO NATION: DNA reveals a staggering range of diversity!"

"Mestizo Genomics" by Peter Wade, et al

MEXICO IS HOT, WITH MARQUEZ VICTORY OVER PACQUAIO!

Mexico is hot and the place to be, with Mexico winning the Olympic Gold in soccer, and now Juan Marquez knocking out Pacquaio.

XOLOS ARE CHAMPIONS!

Tijuana scores two goals just seconds apart in the second half to win the Liga MX title in Toluca, Mexico, setting off a wild celebration back home. "Tijuana was just better than us," said Toluca coach Enrique Meza, whose team was trying to tie Chivas with its 11th Mexican title.